Oct 4 2012

A technique that uses acoustic waves to sort cells on a chip may create miniature medical analytic devices that could make Star Trek's tricorder seem a bit bulky in comparison, according to a team of researchers.

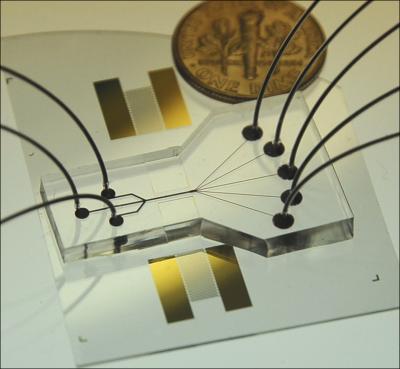

Slightly larger than a dime, this cell-sorting device uses two sound beams to act as acoustic tweezers. Credit: Penn State and Ascent BioNano Technologies

Slightly larger than a dime, this cell-sorting device uses two sound beams to act as acoustic tweezers. Credit: Penn State and Ascent BioNano Technologies

The device uses two beams of acoustic -- or sound -- waves to act as acoustic tweezers and sort a continuous flow of cells on a dime-sized chip, said Tony Jun Huang, associate professor of engineering science and mechanics, Penn State. By changing the frequency of the acoustic waves, researchers can easily alter the paths of the cells.

Huang said that since the device can sort cells into five or more channels, it will allow more cell types to be analyzed simultaneously, which paves the way for smaller, more efficient and less expensive analytic devices.

"Eventually, you could do analysis on a device about the size of a cell phone," said Huang. "It's very doable and we're making in-roads to that right now."

Biological, genetic and medical labs could use the device for various types of analysis, including blood and genetic testing, Huang said.

Most current cell-sorting devices allow the cells to be sorted into only two channels in one step, according to Huang. He said that another drawback of current cell-sorting devices is that cells must be encapsulated into droplets, which complicates further analysis.

"Today, cell sorting is done on bulky and very expensive devices," said Huang. "We want to minimize them so they are portable, inexpensive and can be powered by batteries."

Using sound waves for cell sorting is less likely to damage cells than current techniques, Huang added.

In addition to the inefficiency and the lack of controllability, current methods produce aerosols, gases that require extra safety precautions to handle.

The researchers, who released their findings in the current edition of Lab on a Chip, created the acoustic wave cell-sorting chip using a layer of silicone -- polydimethylsiloxane. According to Huang, two parallel transducers, which convert alternating current into acoustic waves, were placed at the sides of the chip. As the acoustic waves interfere with each other, they form pressure nodes on the chip. As cells cross the chip, they are channeled toward these pressure nodes.

The transducers are tunable, which allows researchers to adjust the frequencies and create pressure nodes on the chip.

The researchers first tested the device by sorting a stream of fluorescent polystyrene beads into three channels. Prior to turning on the transducer, the particles flowed across the chip unimpeded. Once the transducer produced the acoustic waves, the particles were separated into the channels.

Following this experiment, the researchers sorted human white blood cells that were affected by leukemia. The leukemia cells were first focused into the main channel and then separated into five channels.

The device is not limited to five channels, according to Huang.

"We can do more," Huang said. "We could do 10 channels if we want, we just used five because we thought it was impressive enough to show that the concept worked."

Huang worked with Xiaoyun Ding, graduate student, Sz-Chin Steven Lin, postdoctoral research scholar, Michael Ian Lapsley, graduate student, Xiang Guo, undergraduate student, Chung Yu Keith Chan, doctoral student, Sixing Li, doctoral student, all of the Department of Engineering Science and Mechanics at Penn State; Lin Wang, Ascent BioNano Technologies; and J. Philip McCoy, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health.