Aug 11 2009

The smallest organisms to use a biological compass are magnetotactic bacteria, however mysteries remain about exactly how these bacteria create their cellular magnets. In a study published online in Genome Research, scientists have used genome sequencing to unlock new secrets about these magnetic microbes that could accelerate biotechnology and nanotechnology research.

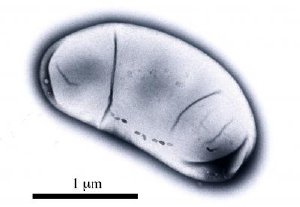

This is a transmission electron micrograph of magnetotactic bacterium, Desulfovibrio magneticus strain RS-1, showing a chain of bullet-shaped magnetosomes aligned along the Earth's magnetic field.

Credit: Image courtesy of Tadashi Matsunaga (Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology).

This is a transmission electron micrograph of magnetotactic bacterium, Desulfovibrio magneticus strain RS-1, showing a chain of bullet-shaped magnetosomes aligned along the Earth's magnetic field.

Credit: Image courtesy of Tadashi Matsunaga (Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology).

Oxygen is essential for human life, but it is corrosive and poisonous to many bacteria. Magnetotactic bacteria evolved a clever method of using the Earth's magnetic field to orient itself and swim downward – exactly the direction a microbe must move to locate low oxygen areas in lakes and oceans. To find the direction of the magnetic field, these bacteria synthesize nanoscale cellular structures called magnetosomes that contain crystals of naturally occurring magnetic minerals.

The shape and composition of magnetosomes are species- and strain-specific, suggesting that magnetosome synthesis is biologically controlled. Magnetosomes are currently difficult to harvest in large quantities or synthesize artificially, therefore deciphering how cells form magnetosomes is crucial if they are to be useful in new technologies.

Genetic analyses have been performed in closely related magnetotactic bacteria, but because magnetosomes are also found in other classes of bacteria, scientists do not yet have a clear picture of the genetic components necessary for magnetosome formation. Tadashi Matsunaga of the Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology and colleagues recognized that by analyzing the genome of more distantly related magnetotactic bacteria, researchers may be able to clearly define the minimal gene set needed for magnetosome synthesis.

In this work, Matsunaga's group sequenced the genome of Desulfovibrio magneticus strain RS-1, a more distant relative of other magnetotactic bacteria previously studied, and is also known for the unique bullet-shape of its magnetosomes. "Understanding the genes that control the morphology of these magnetosomes would be a significant breakthrough," said Matsunaga, noting that RS-1 could be the key to opening up new applications for magnetosomes.

Comparing the RS-1 genome sequence to the genomes of other magnetotactic bacteria, the team determined that all magnetotactic bacteria contain three separate gene regions related to magnetosome synthesis. Surprisingly, they also found that magnetosome-related genes are very well conserved across different classes of bacteria. Matsunaga explained that this suggests that the core magentosome genes may have been established in these bacteria by several horizontal gene transfer events, rather than being passed down through a lineage.

In addition to illuminating core magnetosome genes, the group expects that their work on RS-1 will be a stepping-stone to manipulation of magnetosomes for new technologies. Matsunaga said that further research with RS-1 "could open doors to the synthesis of morphologically controlled magnetosomes, and provide opportunities to their applications in electromagnetic tapes, drug delivery, magnetic resonance imaging, and cell separation."