Jun 9 2014

Scientists at UC Santa Barbara have designed a nanoparticle that has a couple of unique — and important — properties. Spherical in shape and silver in composition, it is encased in a shell coated with a peptide that enables it to target tumor cells. What's more, the shell is etchable so those nanoparticles that don't hit their target can be broken down and eliminated. The research findings appear today in the journal Nature Materials.

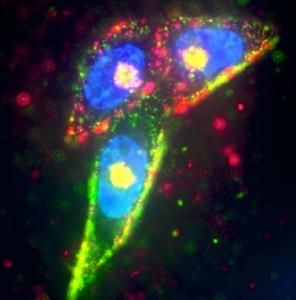

Prostate cancer cells were targeted by two separate silver nanoparticles (red and green), while the cell nucleus was labeled in blueusing Hoescht dye. (Credit: UCSB)

Prostate cancer cells were targeted by two separate silver nanoparticles (red and green), while the cell nucleus was labeled in blueusing Hoescht dye. (Credit: UCSB)

The core of the nanoparticle employs a phenomenon called plasmonics. In plasmonics, nanostructured metals such as gold and silver resonate in light and concentrate the electromagnetic field near the surface. In this way, fluorescent dyes are enhanced, appearing about tenfold brighter than their natural state when no metal is present. When the core is etched, the enhancement goes away and the particle becomes dim.

UCSB's Ruoslahti Research Laboratory also developed a simple etching technique using biocompatible chemicals to rapidly disassemble and remove the silver nanoparticles outside living cells. This method leaves only the intact nanoparticles for imaging or quantification, thus revealing which cells have been targeted and how much each cell internalized.

"The disassembly is an interesting concept for creating drugs that respond to a certain stimulus," said Gary Braun, a postdoctoral associate in the Ruoslahti Lab in the Department of Molecular, Cellular and Developmental Biology (MCDB) and at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute. "It also minimizes the off-target toxicity by breaking down the excess nanoparticles so they can then be cleared through the kidneys."

This method for removing nanoparticles unable to penetrate target cells is unique. "By focusing on the nanoparticles that actually got into cells," Braun said, "we can then understand which cells were targeted and study the tissue transport pathways in more detail."

Some drugs are able to pass through the cell membrane on their own, but many drugs, especially RNA and DNA genetic drugs, are charged molecules that are blocked by the membrane. These drugs must be taken in through endocytosis, the process by which cells absorb molecules by engulfing them.

"This typically requires a nanoparticle carrier to protect the drug and carry it into the cell," Braun said. "And that's what we measured: the internalization of a carrier via endocytosis."

Because the nanoparticle has a core shell structure, the researchers can vary its exterior coating and compare the efficiency of tumor targeting and internalization. Switching out the surface agent enables the targeting of different diseases — or organisms in the case of bacteria — through the use of different target receptors. According to Braun, this should turn into a way to optimize drug delivery where the core is a drug-containing vehicle.

"These new nanoparticles have some remarkable properties that have already proven useful as a tool in our work that relates to targeted drug delivery into tumors," said Erkki Ruoslahti, adjunct distinguished professor in UCSB's Center for Nanomedicine and MCDB department and at Sanford-Burnham Medical Research Institute. "They also have potential applications in combating infections. Dangerous infections caused by bacteria that are resistant to all antibiotics are getting more common, and new approaches to deal with this problem are desperately needed. Silver is a locally used antibacterial agent and our targeting technology may make it possible to use silver nanoparticles in treating infections anywhere in the body."