Aug 12 2014

Nanocubes are anything but child's play. Weizmann Institute scientists have used them to create surprisingly yarn-like strands: They showed that given the right conditions, cube-shaped nanoparticles are able to align into winding helical structures. Their results, which reveal how nanomaterials can self-assemble into unexpectedly beautiful and complex structures, were recently published in Science.

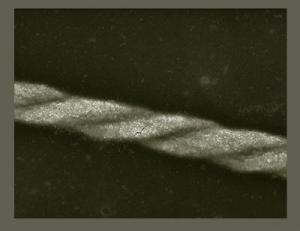

This is an SEM image of a well-defined double helix. Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

This is an SEM image of a well-defined double helix. Credit: Weizmann Institute of Science

Dr. Rafal Klajn and postdoctoral fellow Dr. Gurvinder Singh of the Institute's Organic Chemistry Department used nanocubes of an iron oxide material called magnetite. As the name implies, this material is naturally magnetic: It is found all over the place, including inside bacteria that use it to sense the Earth's magnetic field.

Magnetism is just one of the forces acting on the nanoparticles. Together with the research group of Prof. Petr Král of the University of Illinois, Chicago, Klajn and Singh developed theoretical models to understand how the various forces could push and pull the tiny bits of magnetite into different formations. "Different types of forces compel the nanoparticles to align in different ways," says Klajn. "These can compete with one another; so the idea is to find the balance of competing forces that can induce the self-assembly of the particles into novel materials." The models suggested that the shape of the nanoparticles is important – only cubes would provide a proper balance of forces required for pulling together into helical formations.

The researchers found that the two main competing forces are magnetism and the van der Waals force. Magnetism causes the magnetic particles to both attract and repel one another, prompting the cubic particles to align at their corners. Van der Waals forces, on the other hand, pull the sides of the cubes closer together, coaxing them to line up in a row. When these forces act together on the tiny cubes, the result is the step-like alignment that produces helical structures.

In their experiments, the scientists exposed relatively high concentrations of magnetite nanocubes placed in a solution to a magnetic field. The long, rope-like helical chains they obtained after the solution was evaporated were surprisingly uniform. They repeated the experiment with nanoparticles of other shapes but, as predicted, only cubes had just the right physical shape to align in a helix. Klajn and Singh also found that they could get chiral strands – all wound in the same direction – with very high particle concentrations in which a number of strands assembled closely together. Apparently the competing forces can "take into consideration" the most efficient way to pack the strands into the space.

Although the nanocube strands look nice enough to knit, Klajn says it is too soon to begin thinking of commercial applications. The immediate value of the work, he says, is that it has proven a fundamental principle of nanoscale self-assembly. "Although magnetite has been well-studied – also its nanoparticle form – for many decades, no one has observed these structures before," says Klajn. "Only once we understand how the various physical forces act on nanoparticles can we begin to apply the insights to such goals as the fabrication of previously unknown, self-assembled materials."