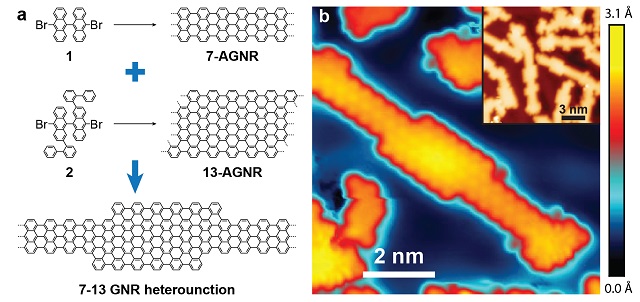

Bottom-up synthesis of graphene nanoribbons from molecular building blocks 1 and 2. (a) The resulting ribbon, or heterojunction, has varied widths as a result of different width molecules 1 and 2. (b) Scanning tunneling microscope image of graphene nanoribbon heterojunction, with larger-scale inset of multiple ribbons.

Bottom-up synthesis of graphene nanoribbons from molecular building blocks 1 and 2. (a) The resulting ribbon, or heterojunction, has varied widths as a result of different width molecules 1 and 2. (b) Scanning tunneling microscope image of graphene nanoribbon heterojunction, with larger-scale inset of multiple ribbons.

A team of researchers from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California, Berkeley have collaborated to develop an accurate method using pre-designed molecular building blocks for synthesizing graphene nanoribbons. The nanoribbons built using this process have position-dependent, tunable bandgaps and other enhanced properties that hold promise for advanced electronic circuitry.

Nanoribbons are narrow strips of graphene. They possess extraordinary properties and hold promise for future nanoelectronic technologies. However, their shape cannot be easily controlled at the atomic scale, and this has prevented their usage for many applications.

This work represents progress towards the goal of controllably assembling molecules into whatever shapes we want. For the first time we have created a molecular nanoribbon where the width changes exactly how we designed it to.

Mike Crommie, senior scientist at Berkeley Lab

“That makes for a nice wire or a simple switching element,” says Crommie, “but it does not provide a lot of functionality. We wanted to see if we could change the width within a single nanoribbon, controlling the structure inside the nanoribbon at the atomic scale to give it new behavior that is potentially useful.”

The molecular components required for checking out this possibility was designed by Felix Fischer, professor of chemistry at UC Berkeley who co led the study. Fischer is also affiliated with the Kavli Energy NanoScience Institute. Fischer and Crommie found out that molecules having various widths could be made to bond chemically, so that the width could be modulated along the resulting nanoribbon’s length.

Think of the molecules as different sized Lego blocks. These blocks have a specific defined structure and when they are pieced together they form a specific shape for the complete nanoribbon. “We want to see if we can understand the exotic properties that emerge when we assemble these molecular structures, and to see if we can exploit them to build new functional devices.

Felix Fischer, professor of chemistry at UC Berkeley

Researchers have so far etched nanoribbons out of larger 2D graphene sheets for nanoribbon synthesis. Fischer states that this is not precise and the final nanoribbon has a random but unique structure. When compared to the “top-down” etching technique, this process yields smoother edges. However, as the nanotubes possess different chiralities and widths, it is difficult to control in this method.

Roman Fasel of Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science & Technology had along with his co-workers discovered a third method. This involved molecule placement on a metal surface, which was followed by fusing them chemically together to form flawless uniform nanoribbons. This approach was modified by Crommie and Fischer. They demonstrated that when constituent molecules shapes were varied then the resulting nanoribbon’s shape also changed.

What we’ve done that is new is to show that it is possible to create atomically-precise nanoribbons with non-uniform shape by changing the shapes of the molecular building blocks.

Mike Crommie, senior scientist at Berkeley Lab

Nanoribbon’s electronic properties, including bandgap, are determined by quantum mechanical standing-wave patterns that are set up by electrons in the nanoribbons. The energetics of electron movement through a nanoribbon is determined by these properties.

Earlier, doping was used to engineer the bandgap of micron-scale devices spatially. However, modifying the width of nanoribbons in sub-nanometer increments is possible for smaller nanoribbons. This has been dubbed as “molecular bandgap engineering” by Crommie and Fischer. This enables researchers to customize the nanoribbon’s quantum mechanical properties, so that they could be used for development of future nanoelectronic devices.

Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) technique was used by Crommie’s group of researchers to test the molecular bandgap engineering. STM can help map electron behavior in a single nanoribbon spatially. “We needed to know the atomic-scale shape of the nanoribbons, and we also needed to know how the electrons inside adapt to that shape,” says Crommie. In order to interpret the STM images correctly, the nanribbon’s electronic structure was calculated by Steven Louie, a senior scientist and Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley Professor of Physics, and Ting Cao, his student. The loop between design, fabrication, and characterization of the nanoribbon was closed by this technique.

An important issue raised by this work is the best way to construct useful devices utilizing these miniscule molecular structures. The research team has so far shown the method to fabricate nanoribbons with varying widths. However, they have not yet included them in real electronic circuits. Crommie and Fischer believe that they would be able to use the nanoribbon for creating more powerful and smaller LEDs, transistors, diodes and other such elements. Finally, they intend to include the nanoribbons in complex circuits for better computer chips. For this, the research team is collaborating with Jeffrey Bokor and Sayeef Salahuddin, who are UC Berkeley electrical engineers.

The spatial precision that is needed already exists. The width of the nanoribbon can be modulated from 0.7 to 1.4nm, and junctions are created in places where the narrow nanoribbons fuse into wider ones seamlessly. “Varying the width by a factor of two allows us to modulate the bandgap by more than 1eV,” says Fischer. This is adequate for building useful devices for many applications.

Crommie states that, the core motivation for this study was to find out the actual behavior of nanoribbons with non-uniform width. “We set out to answer an interesting question, and we answered it,” he concludes.

The researchers have published their study as a paper titled “Molecular bandgap engineering of bottom-up synthesized graphene nanoribbon heterojunctions,” in Nature Nanotechnology.

References