Feb 3 2015

"With the help of magnetic fields, we can selectively create the magnetic nanovortices, then give them a shove so that they are deflected out of their equilibrium position", explains Dr. Felix Büttner, who pursued this research as his Ph.D. project. "We were then able to very precisely track how these skyrmions, as these special nanovortices are called, return to their rest position", Büttner explains further.

The vortices are formed in a magnetic system of thin film multilayers, where alternating layers composed of a cobalt-boron alloy and platinum are stacked on one another. Each individual layer is less than one nanometre thick. This arrangement allows the researchers to very specifically tailor the magnetic properties of the system, enabling the skyrmions to exist. The diameter of these magnetic vortices is no more than 100 nanometres. That is about 1/1000th of the diameter of a human hair.

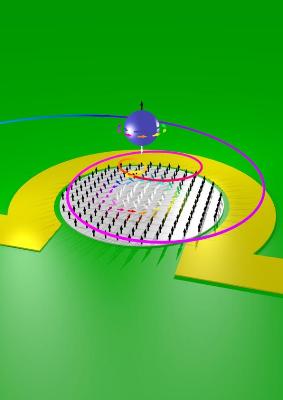

The local magnetisation is depicted by small arrows; a magnetic vortex is located in the centre. A brief current pulse through this nano-wire deflects the skyrmion out of its rest position; it then moves back to its initial position on a spiral trajectory. This motion can be observed with the help of X-ray holography. The skyrmion and the spiral shape of its trajectory are represented schematically above the structure. Credit: TU Berlin

The local magnetisation is depicted by small arrows; a magnetic vortex is located in the centre. A brief current pulse through this nano-wire deflects the skyrmion out of its rest position; it then moves back to its initial position on a spiral trajectory. This motion can be observed with the help of X-ray holography. The skyrmion and the spiral shape of its trajectory are represented schematically above the structure. Credit: TU Berlin

Special techniques enabled the researchers to track the movements of the skyrmions with a precision of better than a few nanometres at individual time steps less than one nanosecond apart. This was facilitated by holographic recording techniques using intense X-ray pulses of the BESSY II synchrotron source at Helmholtz-Zentrum Berlin (HZB). These holographic recording techniques have been developed and improved by the TU Berlin "Nanometre Optics and X-ray Scattering" research group in conjunction with HZB over a number of years, a joint effort directed by Prof. Stefan Eisebitt from TU Berlin.

What Büttner and his co-workers observed in the X-ray holograms was remarkable: "Similar to bumping a spinning top, the nanovortex does not move in a straight line, but instead along a spiral trajectory", explains Büttner. "By comparing our measurements with model calculations, we were able to determine that this spiral-shaped movement can only be explained if the skyrmion has mass."

This is an important discovery, since the nanovortices observed here represent only one special type of skyrmions found in nature. "In the past, skyrmions were often described as being massless", explains Christoforos Moutafis from the Paul Scherrer Institute, who has long been involved with the theoretical description of these kinds of structures. Now, the application of the concept of mass to such particles, as established by this work, will also contribute to the understanding of other types of skyrmions, as the researchers point out in the renowned scientific journal Nature Physics.

There could also be tangible applications for these magnetic nanovortices within thin magnetic layers - they are already being discussed today as an alternative information medium in data processing and storage. Researchers suspect that due to their "skyrmion property", such bits (units of information) can be stored more densely and transferred more reliably than at present. The new insights into skyrmion behaviour might contribute to realising these kinds of novel concepts for information processing.