Mar 19 2015

A new technique to create tissue-engineered bladders has been shown to decrease scarring and significantly increase tissue growth. The bladders are produced using scaffolds coated with anti-inflammatory peptides.

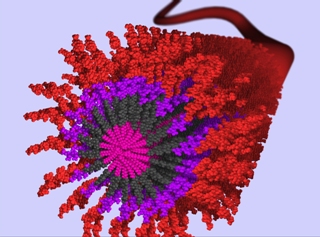

Shown here is a 3D rendering of an anti-inflammatory nanofiber made from self-assembling peptide amphiphile (PA) molecules. Each individual PA molecule is comprised of a hydrophobic alkyl segment (shown by pink) attached to a peptide domain that includes a Beta-sheet forming segment (shown by dark grey). In aqueous environments, these molecules self-assemble through hydrophobic collapse of the alkyl domain in combination with hydrogen bonding in the Beta-sheet domain to produce high aspect-ratio nanofibers. This PA was synthesized to present a bioactive epitope (shown by red) on the nanofiber surface for recognition by cell receptors. The peptide sequence is of special interest in the context of tissue regeneration because the sequence reduces inflammation in damaged tissues. These nanofibers can be coated onto various implant devices and scaffolds to allow for healthy tissue growth. Credit: Mark McClendon

Shown here is a 3D rendering of an anti-inflammatory nanofiber made from self-assembling peptide amphiphile (PA) molecules. Each individual PA molecule is comprised of a hydrophobic alkyl segment (shown by pink) attached to a peptide domain that includes a Beta-sheet forming segment (shown by dark grey). In aqueous environments, these molecules self-assemble through hydrophobic collapse of the alkyl domain in combination with hydrogen bonding in the Beta-sheet domain to produce high aspect-ratio nanofibers. This PA was synthesized to present a bioactive epitope (shown by red) on the nanofiber surface for recognition by cell receptors. The peptide sequence is of special interest in the context of tissue regeneration because the sequence reduces inflammation in damaged tissues. These nanofibers can be coated onto various implant devices and scaffolds to allow for healthy tissue growth. Credit: Mark McClendon

Tissue-engineered organs such as supplemental bladders, small arteries, skin grafts, cartilage, and even a full trachea have been implanted in patients, but the procedures are still experimental, very costly, and often fail.

Scientists and engineers studying tissue engineering face many challenges, but perhaps the greatest is the human immune system. The immune system is very good at sensing, and rejecting, any foreign intrusion into the body. When it senses an intruder, it has a variety of tools to take care of the potential threat. Often, the immune system’s first line of defense is inflammation. That is why after a cut, burn, or twisted ankle, the area around the injury sometimes swells. This can be a helpful response when the body is in danger, but is very frustrating for researchers who are trying to help a patient by introducing engineered tissue, which the body sometimes interprets as a threat. The inflammatory response can cause scarring, which can slow, or even stop, new tissue growth.

Researchers at Northwestern University funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering have found a way that may help reduce the immune system’s inflammatory response. Before they began to grow the tissue, they coated the scaffold, a framework for the tissue to grow around, with anti-inflammatory peptide amphiphiles (AIF-PAs). Peptides are small, naturally occurring biological molecules that are the building blocks of proteins. AIF-PAs are peptide-based molecules that self-assemble into nanofibers. The researchers found that by coating their scaffold with these self-assembling nanofibers, they were able to significantly decrease the amount of inflammation, making it easier for healthy tissue to grow.

The main reason for the decrease in inflammation is the effect that AIF-Pas have on macrophages. Macrophages are the scavenger effectors of the immune systems and are often found in areas of injury. They have many (sometimes conflicting) responses to this complex environment. There is recent evidence that there are two subtypes of macrophages, M1 and M2, which have different roles. M1 macrophages tend to increase the inflammatory response and are often chronic, secreting chemicals that call more M1 macrophage cells to the area. This can cause tissue fibrosis, or scarring, due to the overproduction of collagen. M2 macrophages are less likely to interfere with tissue growth and actually help with proper tissue regeneration.

Arun Sharma, Ph.D., Earl Cheng, M.D., and Samuel Stupp, Ph.D., and their teams at Northwestern’s Simpson Querrey Institute for BioNanotechnology found that by treating their scaffolds with AIF-PAs, they were able to significantly decrease the number of M1 macrophages while still maintaining a stable number of M2 macrophages. This resulted in more growth of functioning bladder tissue with less scarring. In addition, pro-inflammatory cytokine levels decreased while anti-inflammatory cytokines increased, which resulted in fewer cases of tissue granuloma and bladder stone formation.

While the team has focused on the bladder, this technique could be modified and used with many different kinds of engineered tissues that are grown on scaffolds. More research into testing different types of AIF-PAs should allow researchers to better control the tissue regenerative response.