Image Credit: Shutterstock.com / Neon_dust

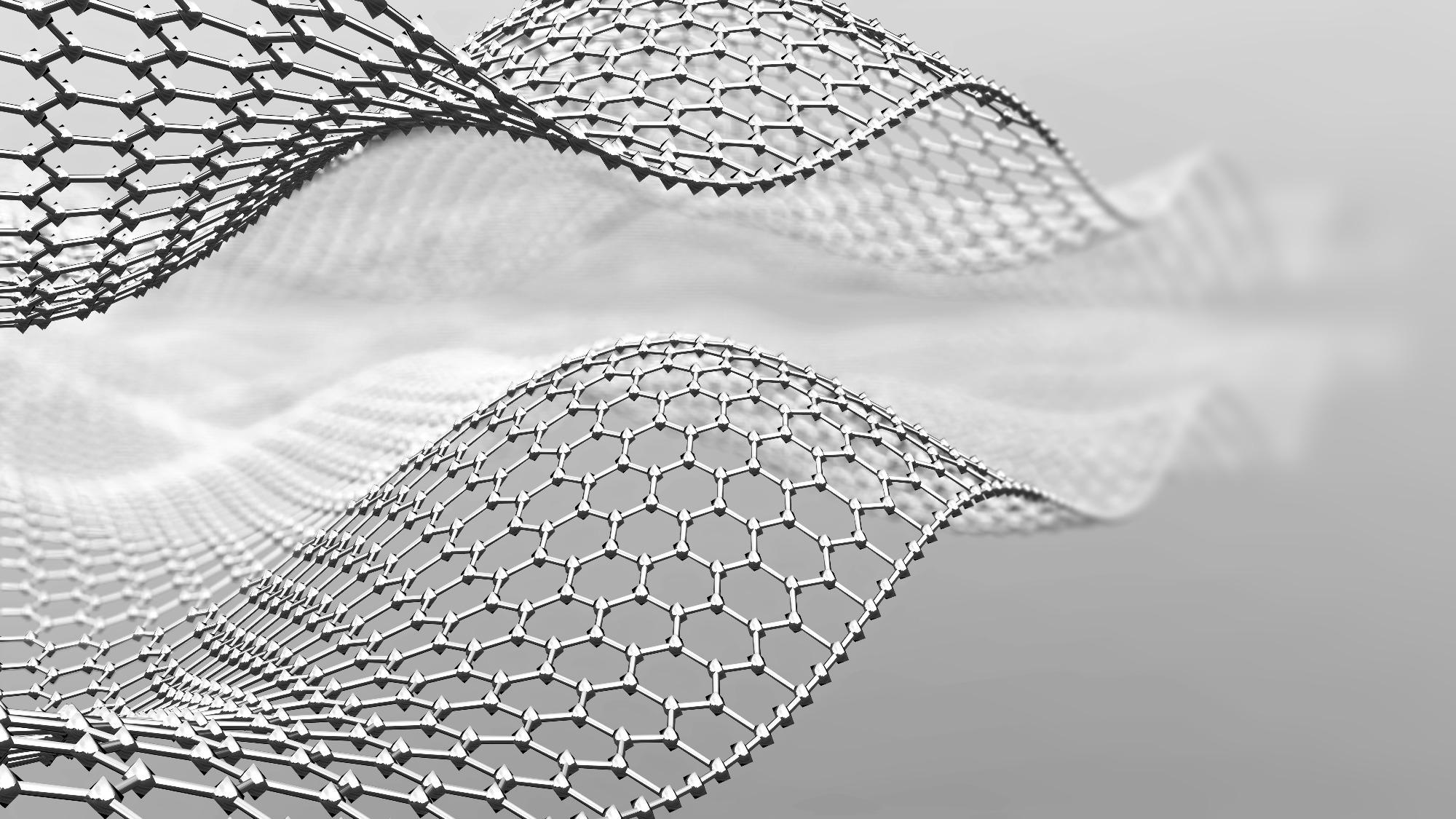

Graphene and other 2D materials could be used to create tiny microchips through a folding process dubbed ‘nano-origami.’ The development could result in a new generation of smaller, faster, and greener ‘straintronic’ devices.

Researchers from the University of Sussex have pioneered a process that creates ‘kinks’ and folds in a 2D sheet of graphene — composed of a single layer of carbon atoms — that could, in turn, be used to create the smallest ever microchips.

The distortions in the graphene result in the nanomaterial adopting the properties of a transistor, the scientists reveal in a paper published in the journal ACS Nano¹. Thus, a strip of graphene that is treated in this way can be fashioned into a microchip that is hundreds of times tinier than those found in current devices.

One of the most obvious and immediate benefits of this technique — which the researchers have dubbed ‘nano-origami’ — is upping the operating speeds of both computers and mobile phones while potentially reducing the size and weight of such devices.

We’re mechanically creating kinks in a layer of graphene. It’s a bit like nano-origami. Using these nanomaterials will make our computer chips smaller and faster.

Alan Dalton, Professor, The School of Mathematical and Physics, The University of Sussex

Dalton refers to this kind of technology as ‘straintronics’ and highlights the fact that the folding process opens up space inside of devices, going on to explain that this development comes at an absolutely critical juncture. This is because computer manufacturers are at the limit of what traditional semiconducting technology can achieve.

Introducing Straintronics

The term ‘straintronics’ refers to an entirely new area of condensed matter physics² in which materials are exposed to physical strain. 2D materials like graphene have long been the subject of straintronics-like ‘deformation experiments’ with the changes demonstrating an influence over both electronic and nanomechanical properties³.

In particular, graphene nanoribbons, when exposed to physical strain, can begin to act as if they are being exposed to a strong magnetic field.

But, so far, those influences have been poorly understood. The University of Sussex team’s findings could begin to clear some of the confusion surrounding graphene and straintronics.

As well as measuring the effects of folding, wrinkling, and collapsing graphene on these properties, the team also employed a technique called nanomechanical atomic force microscopy to investigate how the processes affected the stiffness of the graphene.

Something that could make these straintronic graphene microchips more environmentally friendly as well as giving them the edge over other developing technology.

A Greener Microchip

Graphene is already a material that is renowned for its strength and flexibility as well as its heat and electromagnetic conductivity, but increasing its rigidity by folding it in precise ways means that it can be used in a microchip without the addition of additives.

Instead of having to add foreign materials into a device, we’ve shown we can create structures from graphene and other 2D materials simply by adding deliberate kinks into the structure. By making this sort of corrugation we can create a smart electronic component, like a transistor, or a logic gate.

Dr. Manoj Tripathi, Researcher and Lead Author of the paper, The University of Sussex

Doing away with the need for additional materials in microchips means that in addition to the speed boost, the nano-origami process could deliver a green and sustainable tech-breakthrough.

This potential is boosted by the fact that the microchip can operate at room temperature. This doesn’t just give straintronic devices the benefit of conserving energy, however, it also means they have an advantage over spintronic devices — based on a magnetic effect manifested at the quantum level — which must be operated in ultracold conditions.

“Ultimately, this will make our computers and phones thousands of times faster in the future,” Dalton concludes. “Everything we want to do with computers — to speed them up — can be done by crinkling graphene like this.”

References

1. Tripathi. M., Lee. F., Michail. A., et al, [2021], ‘Structural Defects Modulate Electronic and Nanomechanical Properties of 2D Materials,’ ACS NANO, [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.0c06701]

2. Bukharaev. A. A., Zvezdin. A. K., Pyatatkov. A. P., et al, [2018], ‘Straintronics: a new trend in micro- and nanoelectronics and materials science,’ Advances in Physical Sciences, [https://doi.org/10.3367/UFNe.2018.01.038279

3. Azadparvar. M., Cheraghchi. H., [2019], ‘Straintronics in graphene nanoribbons,’ [arXiv:1912.02017]

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the author expressed in their private capacity and do not necessarily represent the views of AZoM.com Limited T/A AZoNetwork the owner and operator of this website. This disclaimer forms part of the Terms and conditions of use of this website.