Jun 2 2008

New research shows that while engineered nanomaterials can be transferred up the lowest levels of the food chain from single celled organisms to higher multicelled ones, the amount transferred was relatively low and there was no evidence of the nanomaterials concentrating in the higher level organisms. The preliminary results observed by researchers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) suggest that the particular nanomaterials studied may not accumulate in invertebrate food chains.

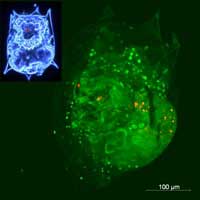

Closeup photomicrograph of rotifer B. calyciflorus (whole organism seen in upper left corner) with quantum dots assimilated from ingested ciliates appearing red. Credit: NIST

Closeup photomicrograph of rotifer B. calyciflorus (whole organism seen in upper left corner) with quantum dots assimilated from ingested ciliates appearing red. Credit: NIST

The same properties that make engineered nanoparticles attractive for numerous applications—biological and environmental stability, small size, solubility in aqueous solutions and lack of toxicity to whole organisms—also raise concerns about their long-term impact on the environment. NIST researchers wanted to determine if nanoparticles could be passed up a model food chain and if so, did the transfer lead to a significant amount of bioaccumulation (the increase in concentration of a substance in an organism over time) and biomagnification (the progressive buildup of a substance in a predator organism after ingesting contaminated prey).

In their study, the NIST team investigated the dietary accumulation, elimination and toxicity of two types of fluorescent quantum dots using a simple, laboratory-based food chain with two microscopic aquatic organisms—Tetrahymena pyriformis, a single-celled ciliate protozoan, and the rotifer Brachionus calyciflorus that preys on it. The process of a material crossing different levels of a food chain from prey to predator is called "trophic transfer."

Quantum dots are nanoparticles engineered to fluoresce strongly at specific wavelengths. They are being studied for a variety of uses including easily detectable tags for medical diagnostics and therapies. Their fluorescence was used to detect the presence of quantum dots in the two microorganisms.

The researchers found that both types of quantum dots were taken in readily by T. pyriformis and that they maintained their fluorescence even after the quantum dot-containing ciliates were ingested by the higher trophic level rotifers. This observation helped establish that the quantum dots were transferred across the food chain as intact nanoparticles and that dietary intake is one way that transfer can occur. The researchers noted that, "Some care should be taken, however, when extrapolating our laboratory-derived results to the natural environment."

"Our findings showed that although trophic transfer of quantum dots did take place in this simple food chain, they did not accumulate in the higher of the two organisms," says lead author David Holbrook. "While this suggests that quantum dots may not pose a significant risk of accumulating in aquatic invertebrate food chains in nature, additional research beyond simple laboratory experiments and a more exact means of quantifying transferred nanoparticles in environmental systems are needed to be certain."