Aug 21 2008

It's estimated that the red tide algae, Karenia brevis, costs approximately $20 million per bloom in economic damage off the coast of Florida alone. Scientists at the Georgia Institute of Technology have found that a diatom can reduce the levels of the red tide's toxicity to animals and that the same diatom can reduce red tide's toxicity to other algae as well. If scientists can learn to use this process to reduce the toxicity of red tide, they could reduce the vast amount of economic damage done to the seafood and tourism industries. The research appears as articles in press for the Web sites of the journals Harmful Algae and the Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B.

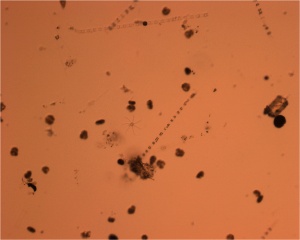

Skeletonema costatum (the chain-like organism) has been found to reduce the toxicity of the red tide organism (the round cells) to both animals and other algae.

Skeletonema costatum (the chain-like organism) has been found to reduce the toxicity of the red tide organism (the round cells) to both animals and other algae.

“We found that red tide toxins can be metabolized by other species of phytoplankton. That holds true for both the brevetoxins that damage members of the animal kingdom and the as yet unknown allelopathic toxins that kill other competing species of algae,” said Julia Kubanek, an associate professor with a joint appointment in Georgia Tech's School of Biology and School of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

Red tide is a dramatic case of an ecosystem that's out of control. In normal seawater, K. brevis makes up about 1 percent or less of the species, but during a red tide, that share increases to more than 90 percent. Filter feeders such as oysters, mussels and clams ingest the dinoflagellate and become unsafe to eat. Fish killed by the red tide wash on the shore, which can be contaminated and essentially unusable to tourists for months at a time.

Kubanek and her researchers found in previous work that the growth of the diatom Skeletonema costatum was only moderately suppressed by the brevetoxins released by the red tide. So, they figured that the diatom might have a way to deal with the toxins. According to their study, they were right.

In one experiment, detailed in the journal Harmful Algae, Kubanek's students grew the red tide algae along with the S. costatum diatom to test her group's hypothesis and found that the samples with both organisms had a smaller concentration of brevetoxin B than samples without the diatom. They also tested the algae with four different S. costatum diatom strains from around the world and came up with largely the same results. That suggests that evolutionary experience with the red tide algae was not necessary for the diatom to resist the toxins.

In another experiment, covered in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, they found that the red tide algae was able to reduce the growth of the S. costatum diatom, but that exposure of the red tide organism to S. costatum makes the red tide less toxic to microscopic algae. That suggests that the diatom is somehow able to reduce the potency of red tide's toxins.

“It could be that Skeletonema is degrading Karenia's allelopathic chemicals just like it degrades brevetoxins. Or, it could be that Skeletonema is stressing Karenia out, making it harder to produce allelopathic chemicals,” said Kubanek.

What they do know is that the brevetoxins that harm oysters and other members of the animal kingdom aren't the whole story.

“We found that when we took seawater and added purified brevetoxins to it, the live algae didn't suffer much, so there must be other chemicals released by the red tide that are toxic to these algae,” said Kubanek.

How that's done, isn't clear yet, but Kubanek and her group are currently working on finding the answer to that question.

“What we do know is that this diatom, S. costatum, is able to undermine these toxins produced by the red tide, as well as the brevetoxins that are known to kill vertebrate animals like fish and dolphins,” said Kubanek.

If scientists such as Kubanek and her team can learn more about the strategies that microscopic algae use to reduce the toxicity of red tide, they might be able to use that knowledge to help reduce the poisonous effects the tide has on the animal kingdom, not to mention the damage it does to the seafood and tourism industries.

Kubanek's research team for these studies consisted of Tracey Myers and Emily Prince from Georgia Tech and Jerome Naar of the Center for Marine Science at the University of North Carolina at Wilmington.