Apr 7 2009

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) and Cornell University have capitalized on a process for manufacturing integrated circuits at the nanometer (billionth of a meter) level to engineer the first-ever nanoscale fluidic device with complex three-dimensional surfaces. As described in a recent paper in the journal Nanotechnology,* the Lilliputian chamber is a prototype for future tools with custom-designed surfaces to manipulate and measure different types of nanoparticles in solution.

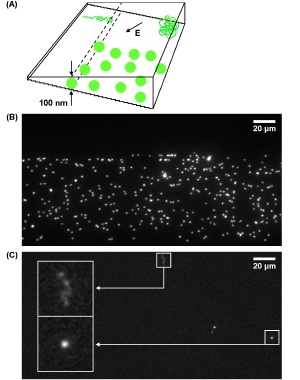

(A) Schematic of the NIST-Cornell nanofluidic device with complex 3-D surfaces. Each “step” of the “staircase” seen on the side marks a different depth within the chamber. The letter “E” shows the direction of the electric field used to move the nanoparticles through the device. The green balls are spheres with diameters of 100 nanometers whose size restricts them from moving into the shallower regions of the chamber. The coil in the deep end of the chamber (upper right corner) is a single DNA strand that elongates (upper left corner) in the shallow end.

(B) Photomicrograph showing fluorescently tagged spherical nanoparticles stopped at the 100-nanometer level of the chamber, the depth that corresponds to their diameter.

(C) Photomicrograph of a single DNA strand that is coiled in the deep end of chamber (box at far right) and elongated in the shallow end (box at far left). Larger boxes are closeups showing the fluorescently tagged strands. Credit: NIST

(A) Schematic of the NIST-Cornell nanofluidic device with complex 3-D surfaces. Each “step” of the “staircase” seen on the side marks a different depth within the chamber. The letter “E” shows the direction of the electric field used to move the nanoparticles through the device. The green balls are spheres with diameters of 100 nanometers whose size restricts them from moving into the shallower regions of the chamber. The coil in the deep end of the chamber (upper right corner) is a single DNA strand that elongates (upper left corner) in the shallow end.

(B) Photomicrograph showing fluorescently tagged spherical nanoparticles stopped at the 100-nanometer level of the chamber, the depth that corresponds to their diameter.

(C) Photomicrograph of a single DNA strand that is coiled in the deep end of chamber (box at far right) and elongated in the shallow end (box at far left). Larger boxes are closeups showing the fluorescently tagged strands. Credit: NIST

Among the potential applications are processing nanoscale materials for manufacturing products such as pharmaceuticals, sorting mixtures of nanoparticles for environmental health and safety investigations, and isolating and confining individual DNA strands for scientific study.

Nanofluidic devices are usually fabricated by etching tiny channels into a glass or silicon wafer with the same “lithographic” procedures used for making integrated circuits. To date, these flat rectangular channels have had simple surfaces with only a few depths. This limits their ability to separate mixtures of nanoparticles with different sizes or study the nanoscale behavior of biomolecules (such as DNA) in detail.

To solve the problem, the researcher team developed a lithographic process to fabricate complex 3-D surfaces. To demonstrate their method, they constructed a nanofluidic chamber with a “staircase” geometry etched into the floor. The “steps” in this staircase—each level giving the device a progressively increasing depth from 10 nanometers (about 6,000 times smaller than the width of a human hair) at the top to 620 nanometers at the bottom—are what give the device its ability to manipulate nanoparticles by size in the same way a coin sorter separates nickels, dimes and quarters.

In these novel experiments, the researchers tested their device with two different solutions: one containing 100-nanometer-diameter polystyrene spheres and the other containing 20-micrometer (millionth of a meter)-length DNA molecules from a virus. In each experiment, the researchers injected the solution into the chamber’s deep end and then used electric fields to drive their sample across the device from deeper to shallower levels. Both the spheres and DNA strands were tagged with fluorescent dye so that their movements could be tracked with a microscope.

In the trials using rigid nanoparticles, size exclusion occurred when the region of the chamber where the channels were less than 100 nanometers in depth stayed free of the particles. In the viral DNA trials, the genetic material was coiled in the deeper channels and elongated when forced into the shallower ones. These results demonstrate the utility of the NIST-Cornell 3-D nanofluidic device to perform more complicated nanoscale operations.

Currently, the researchers are working to separate and measure mixtures of different-sized nanoparticles and investigate the behavior of DNA captured in a 3-D nanofluidic environment. For more information and images, see “NIST-Cornell Team Builds World’s First Nanofluidic Device with Complex 3-D Surfaces.”

* S.M. Stavis, E.A. Strychalski and M.Gaitan. Nanofluidic structures with complex three-dimensional surfaces. Nanotechnology Vol. 20, Issue 16 (online March 31, 2009; in print April 22, 2009).