Scientists from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) have come up with a new kind of printing process that involves the elimination of material instead of depositing it. The method could be, specifically, beneficial for printing banknotes and ID documents, for instance.

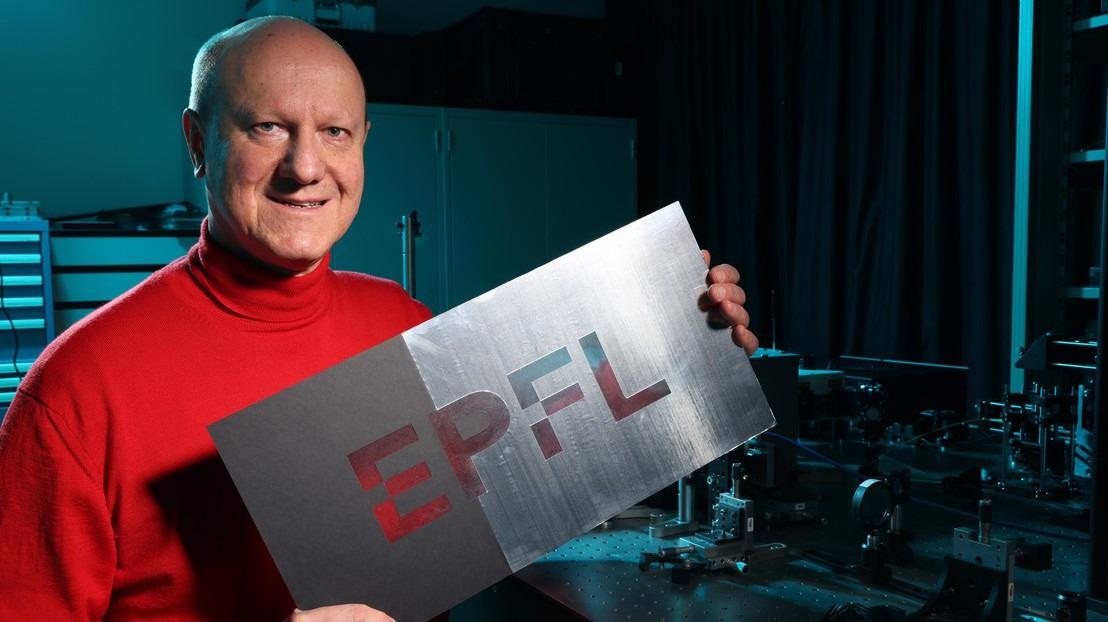

Image Credit Olivier Martin © Alain Herzog 2022 École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne.

We’ve developed an entirely new printing process, turning Gutenberg’s concept on its head.

Olivier Martin, Professor and Head, Nanophotonics and Metrology Laboratory, School of Engineering, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne

Martin proudly puts forth a representation of EPFL’s logo achieved with the help of this method discovered by his team. The letters present in the logo seem to be transparent, while their edges appear to be black or aluminum-colored.

The initial aim of the scientist was to develop a material that could exhibit the ability to absorb light fully. They made a material composed of three layers—first aluminum, then magnesium fluoride (a dielectric compound), and followed by chrome—sitting on a Plexiglas substrate.

Each layer just measures a thickness of a few nanometers. The final result is a black surface that will absorb all light waves.

Black is a really hard color to obtain. You usually end up with something that has either bluish or violet undertones. But in our case, the black we obtained was truly black. That means our material can capture 100% of the light it’s exposed to.

Olivier Martin, Professor and Head, Nanophotonics and Metrology Laboratory, School of Engineering, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne

A Perfect Mirror

Sebastian Mader, the PhD student who headed the project, wished to see what would occur if he removed the top layer of the material called the chrome.

Mader stated, “Once I did that, all that was left was the dielectric compound and the aluminum. Together, these two compounds form a perfect mirror. They reflect all wavelengths of light, absorbing none of it. That gave us a fully transparent surface.”

He then removed these two layers, thereby leaving only the Plexiglas substrate.

Drawing Transparency

With the help of a laser, the scientists eliminated the individual layers. It was highly accurate that they were able to thin the layers out as considerably or little as they wished to reproduce the complete spectrum of shades present between black and transparent.

“The longer we left the laser on a given spot, the more material it removed,” says Martin.

We basically ‘drew’ lines of transparency rather than lines of color. Contrast is very important for our eyes, and since our method can produce both fully black and fully transparent areas, we can generate a lot of contrast. For instance, we can draw white letters on a black background, making the letters very easy to read.

Olivier Martin, Professor and Head, Nanophotonics and Metrology Laboratory, School of Engineering, École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne

Their new technique could be particularly useful in security applications and printing banknotes.

Journal Reference:

Mader, S & Martin, O. J. F (2021) Engineering multi-state transparency on demand. Light: Advanced Manufacturing. doi.org/10.37188/lam.2021.026.