Mar 15 2013

In the military, collateral damage means innocent civilians dying. In medicine, it means side effects – and that can mean death for the patient.

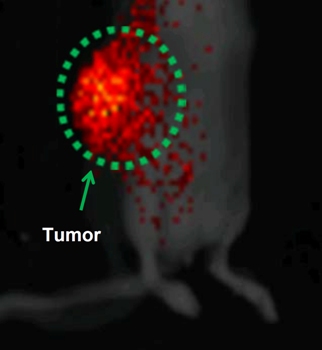

"Peisheng Xu at the University of South Carolina is developing “smart” drugs. In this fluorescence image, a tumor in a mouse is specifically targeted by an injected nanoparticle, shown in red."

"Peisheng Xu at the University of South Carolina is developing “smart” drugs. In this fluorescence image, a tumor in a mouse is specifically targeted by an injected nanoparticle, shown in red."

But Peisheng Xu of the University of South Carolina is helping craft new pharmaceuticals that could dramatically improve a patient’s odds when heavy-duty drugs are prescribed. Xu’s research is focused on developing drugs with the kind of precision that the military seeks with smart bombs.

Xu’s team is perfecting drugs with two molecular parts – one that functions as a guiding mechanism, and the other as a warhead. When it comes to cancer, for example, the drugs are designed to move through the human body rather innocuously, ignoring the many good cells that make up a healthy human body.

But things quickly change when one of these two-headed drugs finds a bad guy. The drug enters the offending cell and unloads the pharmaceutical warhead, serving up a cellular annihilation that tumor cells so richly deserve.

One beauty of the approach is that many molecular warheads have already been developed.

“Lots of drugs are very effective in killing cancer cells, but when they kill cancer cells, they also kill healthy cells, or damage healthy cells,” said Xu, a researcher in the South Carolina College of Pharmacy. “Doxorubicin, for example, is a very powerful anticancer drug, but it will also cause heart damage – a patient can only use a certain amount of that drug over a lifetime, otherwise the patient will have heart problems.”

A polymer chemist, Xu leads a team of scientists that crafts a polymer coating, or carrier, for a drug like doxorubicin. The coating encapsulates the powerful anticancer agent, rendering it harmless until released. The polymer coating also has design features that help the drug find a tumor cell, work its way inside it, and only then release the anticancer cargo.

“The carrier I’m using is a nanoparticle,” Xu said. “It has a size about 1,000 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair.”

Working with colleagues Remant K.C. and Bindu Thapa at USC, Xu published a paper in Molecular Pharmaceutics (released online Aug. 9, 2012) detailing a nanoparticle polymer containing a 2-(pyridin-2-yldisulfanyl) side chain that reliably releases a doxorubicin cargo after moving from an extracellular environment to an intracellular one. The polymer also has other molecular “handles” to which the chemists can attach cellular targeting moieties.

Xu and K.C. followed up with a paper in the Dec. 18, 2012 issue of Advanced Materials that shows how to use both doxorubicin and paclitaxel to provide a “cocktail therapy” option with their drugs, achieving a strong synergistic effect. The American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy has taken notice, awarding Xu a highly competitive New Investigator Award in 2012.

And it’s not just cancer that Xu has his eye on. “We’re trying to extend the work into other areas as well, such as diseases of the central nervous system – Alzheimer’s disease – and liver disease,” he said. “We’ve also just begun a collaboration involving cardiovascular disease. The goal of my research is to give the patient the right drug, to the right tissue, to the right cell, in the right dose, at the right time.”