Apr 3 2009

Some of the brightest colors in nature are created by tiny nanostructures with a structure similar to beer foam or a sponge, according to Yale University researchers.

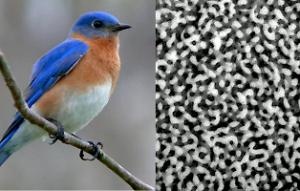

Prum and Dufresne discovered that the nanostructures that produce some birds’ brightly colored plumage, such as the blue feathers of the male Eastern Bluebird, have a sponge-like structure. (Credit: Photo by Ken Thomas)

Prum and Dufresne discovered that the nanostructures that produce some birds’ brightly colored plumage, such as the blue feathers of the male Eastern Bluebird, have a sponge-like structure. (Credit: Photo by Ken Thomas)

Most colors in nature—from the color of our skin to the green of trees—are produced by pigments. But the bright blue feathers found in many birds, such as Bluebirds and Blue Jays, are instead produced by nanostructures. Under an electron microscope, these structures look like sponges with air bubbles.

Now an interdisciplinary team of Yale engineers, physicists and evolutionary biologists has taken a step toward uncovering how these structures form. They compared the nanostructures to examples of materials undergoing phase separation, in which mixtures of different substances become unstable and separate from one another, such as the carbon-dioxide bubbles that form when the top is popped off a bubbly drink. They found that the color-producing structures in feathers appear to self-assemble in much the same manner. Bubbles of water form in a protein-rich soup inside the living cell and are replaced with air as the feather grows.

The research, which appears online in the journal Soft Matter, provides new insight into how organisms use self-assembly to produce color, and has important implications for the role color plays in birds’ plumage, as the color produced depends entirely on the precise size and shape of these nanostructures.

“Many biologists think that plumage color can encode information about quality – basically, that a bluer male is a better mate,” said Richard Prum, chair of the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and one of the paper’s authors. “Such information would have to be encoded in the feather as the bubbles grow. I think our hypothesis that phase separation is involved provides less opportunity for encoding information about quality than most biologists thought. At the same time, it’s exciting to think about other ways birds might be using phase separation.”

Eric Dufresne, lead author of the paper, is also interested in the potential technological applications of the finding. “We have found that nature elegantly self assembles intricate optical structures in bird feathers. We are now mimicking this approach to make a new generation of optical materials in the lab,” said Dufresne, assistant professor of mechanical engineering, chemical engineering and physics.

Prum believes it was the interdisciplinary approach the team took that led to their success – a result he plans on celebrating “with another practical application of phase separation: champagne!”

Other authors of the paper include Heeso Noh, Vinodkumar Saranathan, Simon Mochrie Hui Cao (all of Yale University).