Jul 7 2009

Tiny flying machines can be used for everything from indoor surveillance to exploring collapsed buildings, but simply making smaller versions of planes and helicopters doesn't work very well. Instead, researchers at North Carolina State University are mimicking nature's small flyers - and developing robotic bats that offer increased maneuverability and performance.

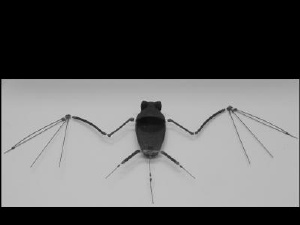

The skeleton of the robotic bat uses shape-memory metal alloy that is super-elastic for the joints, and smart materials that respond to electric current for the muscular system. Credit: Gheorghe Bunget, North Carolina State University.

The skeleton of the robotic bat uses shape-memory metal alloy that is super-elastic for the joints, and smart materials that respond to electric current for the muscular system. Credit: Gheorghe Bunget, North Carolina State University.

Small flyers, or micro-aerial vehicles (MAVs), have garnered a great deal of interest due to their potential applications where maneuverability in tight spaces is necessary, says researcher Gheorghe Bunget. For example, Bunget says, "due to the availability of small sensors, MAVs can be used for detection missions of biological, chemical and nuclear agents." But, due to their size, devices using a traditional fixed-wing or rotary-wing design have low maneuverability and aerodynamic efficiency.

So Bunget, a doctoral student in mechanical engineering at NC State, and his advisor Dr. Stefan Seelecke looked to nature. "We are trying to mimic nature as closely as possible," Seelecke says, "because it is very efficient. And, at the MAV scale, nature tells us that flapping flight – like that of the bat – is the most effective."

The researchers did extensive analysis of bats' skeletal and muscular systems before developing a "robo-bat" skeleton using rapid prototyping technologies. The fully assembled skeleton rests easily in the palm of your hand and, at less than 6 grams, feels as light as a feather. The researchers are currently completing fabrication and assembly of the joints, muscular system and wing membrane for the robo-bat, which should allow it to fly with the same efficient flapping motion used by real bats.

"The key concept here is the use of smart materials," Seelecke says. "We are using a shape-memory metal alloy that is super-elastic for the joints. The material provides a full range of motion, but will always return to its original position – a function performed by many tiny bones, cartilage and tendons in real bats."

Seelecke explains that the research team is also using smart materials for the muscular system. "We're using an alloy that responds to the heat from an electric current. That heat actuates micro-scale wires the size of a human hair, making them contract like 'metal muscles.' During the contraction, the powerful muscle wires also change their electric resistance, which can be easily measured, thus providing simultaneous action and sensory input. This dual functionality will help cut down on the robo-bat's weight, and allow the robot to respond quickly to changing conditions – such as a gust of wind – as perfectly as a real bat."

In addition to creating a surveillance tool with very real practical applications, Seelecke says the robo-bat could also help expand our understanding of aerodynamics. "It will allow us to do tests where we can control all of the variables – and finally give us the opportunity to fully understand the aerodynamics of flapping flight," Seelecke says.

Bunget will present the research this September at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers Conference on Smart Materials, Adaptive Structures and Intelligent Systems in Oxnard, Calif.