In a new approach to an effective "electronic tongue" that mimics human taste, scientists in Illinois are reporting development of a small, inexpensive, lab-on-a-chip sensor that quickly and accurately identifies sweetness - one of the five primary tastes. It can identify with 100 percent accuracy the full sweep of natural and artificial sweet substances, including 14 common sweeteners, using easy-to-read color markers. This sensory "sweet-tooth" shows special promise as a simple quality control test that food processors can use to ensure that soda pop, beer, and other beverages taste great, - with a consistent, predictable flavor. Their study was described here today at the American Chemical Society's 238th National Meeting.

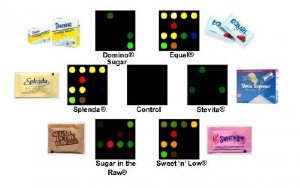

In an advance toward a long-awaited "electronic tongue," a new sensor can detect up to 14 commonly-used sweeteners. The device shows promise for quality control monitoring in the food and beverage industry. Credit: Kenneth Suslick, Ph.D., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

In an advance toward a long-awaited "electronic tongue," a new sensor can detect up to 14 commonly-used sweeteners. The device shows promise for quality control monitoring in the food and beverage industry. Credit: Kenneth Suslick, Ph.D., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

The new sensor, which is about the size of a business card, can also identify sweeteners used in solid foods such as cakes, cookies, and chewing gum. In the future, doctors and scientists could use modified versions of the sensor for a wide variety of other chemical-sensing applications ranging from monitoring blood glucose levels in people with diabetes to identifying toxic substances in the environment, the researchers say.

"We take things that smell or taste and convert their chemical properties into a visual image," says study leader Kenneth Suslick, Ph.D., of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "This is the first practical "electronic tongue" sensor that you can simply dip into a sample and identify the source of sweetness based on its color."

Researchers have tried for years to develop "electronic tongues" or "electronic noses" that rival or even surpass the sensitivity of the human tongue and nose. But these devices can generally have difficulty distinguishing one chemical flavor from another, particularly in a complex mixture. Those drawbacks limit the practical applications of prior technology.

Suslick's team has spent a decade developing "colorimetric sensor arrays" that may fit the bill. The "lab-on-a-chip" consists of a tough, glass-like container with 16 to 36 tiny printed dye spots, each the diameter of a pencil lead. The chemicals in each spot react with sweet substances in a way that produces a color change. The colors vary with the type of sweetener present, and their intensity varies with the amount of sweetener.

To the scientists' delight, the sensor identified 14 different natural and artificial sweeteners, including sucrose (table sugar), xylitol (used in sugarless chewing gum), sorbitol, aspartame, and saccharin with 100 percent accuracy in 80 different trials.

Many food processors use a test called high-pressure liquid chromatography to measure sweeteners for quality control. But it requires an instrument the size of a desk that costs tens of thousands of dollars and needs a highly trained technician to operate. The process is also relatively slow, taking up to 30 minutes. The new sensor, in contrast, is small, inexpensive, disposable, and produces results in about 2 minutes.

Those minutes can be critical. Suclick noted that the food and beverage industry takes great care to ensure consistent quality of the many products that use sweeteners. At present, when a product's taste falls below specifications, then samples must be taken to the lab for analysis. Meanwhile, the assembly lines continue to whirl, with thousands of packages moving along each minute.

"With this device, manufacturers can fix the problem immediately - on location and in real-time," Suslick says.

Christopher Musto, a doctoral student in Suslick's lab, says it will take more work to develop the technology into a complete electronic tongue. "To be considered a true electronic tongue, the device must detect not just sweet, but sour, salty, bitter, and umami - the five main human tastes," he says. Umami means meaty or savory.

The National Institutes of Health funded the research. An Illinois-based company, iSense, is commercializing the technology. Sung H. Lim also contributed to the research study.