Physicists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have built an enhanced version of an experimental atomic clock based on a single aluminum atom that is now the world's most precise clock, more than twice as precise as the previous pacesetter based on a mercury atom.

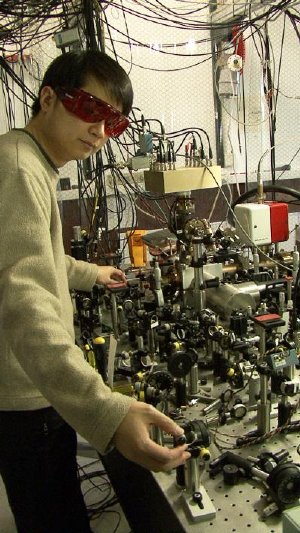

NIST postdoctoral researcher James Chin-wen Chou with the world's most precise clock, based on the vibrations of a single aluminum ion (electrically charged atom). The ion is trapped inside the metal cylinder (center right). Credit: J. Burrus/NIST

NIST postdoctoral researcher James Chin-wen Chou with the world's most precise clock, based on the vibrations of a single aluminum ion (electrically charged atom). The ion is trapped inside the metal cylinder (center right). Credit: J. Burrus/NIST

The new aluminum clock would neither gain nor lose one second in about 3.7 billion years, according to measurements to be reported in Physical Review Letters.*

The new clock is the second version of NIST's "quantum logic clock," so called because it borrows the logical processing used for atoms storing data in experimental quantum computing, another major focus of the same NIST research group. (The logic process is described at http://www.nist.gov/public_affairs/releases/logic_clock/logic_clock.html#background.) The second version of the logic clock offers more than twice the precision of the original.

"This paper is a milestone for atomic clocks" for a number of reasons, says NIST postdoctoral researcher James Chou, who developed most of the improvements.

In addition to demonstrating that aluminum is now a better timekeeper than mercury, the latest results confirm that optical clocks are widening their lead—in some respects—over the NIST-F1 cesium fountain clock, the U.S. civilian time standard, which currently keeps time to within 1 second in about 100 million years.

Because the international definition of the second (in the International System of Units, or SI) is based on the cesium atom, cesium remains the "ruler" for official timekeeping, and no clock can be more accurate than cesium-based standards such as NIST-F1.

The logic clock is based on a single aluminum ion (electrically charged atom) trapped by electric fields and vibrating at ultraviolet light frequencies, which are 100,000 times higher than microwave frequencies used in NIST-F1 and other similar time standards around the world. Optical clocks thus divide time into smaller units, and could someday lead to time standards more than 100 times as accurate as today's microwave standards. Higher frequency is one of a variety of factors that enables improved precision and accuracy.

Aluminum is one contender for a future time standard to be selected by the international community. NIST scientists are working on five different types of experimental optical clocks, each based on different atoms and offering its own advantages. NIST's construction of a second, independent version of the logic clock proves it can be replicated, making it one of the first optical clocks to achieve that distinction. Any future time standard will need to be reproduced in many laboratories.

NIST scientists evaluated the new logic clock by probing the aluminum ion with a laser to measure the exact "resonant" frequency at which the ion jumps to a higher-energy state, carefully accounting for all possible deviations such as those caused by ion motions. No measurement is perfect, so the clock's precision is determined based on how closely repeated measurements can approach the atom's exact resonant frequency. The smaller the deviations from the true value of the resonant frequency, the higher the precision of the clock.

Physicists also evaluate the performance of new optical clocks by comparing them to older optical clocks. In this case, NIST scientists compared their two logic clocks by using the resonant laser frequency from one clock to probe the ion in the other clock. Fifty-six separate comparisons were made, each lasting between 15 minutes and 3 hours.

The two logic clocks exhibit virtually identical "tick" rates—differences don't show up until measurements are extended to 17 decimal places. The agreement between the two aluminum clocks is more than 10 times closer than any previous two-clock comparison, with the lowest measurement uncertainty ever achieved in such an evaluation, according to the paper.

The enhanced logic clock differs from the original version in several ways. Most importantly, it uses a different type of "partner" ion to enable more efficient operations. Aluminum is an exceptionally stable source of clock ticks but its properties are not easily manipulated or detected with lasers. In the new clock, a magnesium ion is used to cool the aluminum and to signal its ticks. The original version of the clock used beryllium, a smaller and lighter ion that is a less efficient match for aluminum.

Clocks have myriad applications. The extreme precision offered by optical clocks is already providing record measurements of possible changes in the fundamental "constants" of nature, a line of inquiry that has important implications for cosmology and tests of the laws of physics, such as Einstein's theories of special and general relativity. Next-generation clocks might lead to new types of gravity sensors for exploring underground natural resources and fundamental studies of the Earth. Other possible applications may include ultra-precise autonomous navigation, such as landing planes by GPS.