Nov 4 2010

Patricia Thiel of Iowa State University and the Ames Laboratory put a box of tissues to the right, a stack of coasters to the middle and a trinket box to the left.

"Nature," she said of her table-top illustration, "doesn't want lots of little things." So Thiel grabbed the smaller things and slid them into a single pile next to the bigger tissue box. "Nature wants one big thing all together, like this."

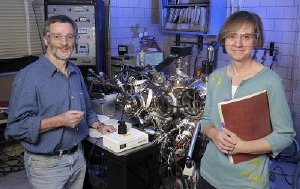

James Evans and Patricia Thiel, of Iowa State University and the US Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory, are using scanning tunneling microscope technology to study coarsening. Understanding the process could improve the stability of nanoscale technologies. Credit: Photo by Bob Elbert/Iowa State University

James Evans and Patricia Thiel, of Iowa State University and the US Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory, are using scanning tunneling microscope technology to study coarsening. Understanding the process could improve the stability of nanoscale technologies. Credit: Photo by Bob Elbert/Iowa State University

Thiel, an Iowa State Distinguished Professor of Chemistry and a faculty scientist for the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory, and James Evans, an Iowa State professor of physics and astronomy and a faculty scientist for the Ames Laboratory, describe that process in the Oct. 29 issue of the journal Science.

The paper, "A Little Chemistry Helps the Big Get Bigger," is in the journal's Perspectives section. It describes a process called coarsening. That's when "a group of objects of different sizes transforms into fewer objects with larger average size, such that 'the big get bigger,'" says the paper. Examples of the process include the geologic formation of gemstones, the degradation of pharmaceutical suspensions and the manufacture of structural steels.

Thiel and Evans were invited to write the paper after Thiel delivered a talk at an American Chemical Society meeting about their studies of coarsening, an emerging field in surface chemistry.

Thiel worked with Mingmin Shen, a former Iowa State doctoral student who is now a post-doctoral research associate at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory in Richland, Wash., on the experimental side of the coarsening research. Evans worked with Da-Jiang Liu, an associate scientist at the Ames Laboratory, on the theoretical side of the project.

The researchers, with the support of grants from the National Science Foundation, have been using scanning tunneling microscope technology – an instrument that allows them to see individual atoms – to study how coarsening happens on the surface of objects.

They've studied nanoscale particles grown on the surface of silver and how adding sulfur can increase coarsening. They're trying to learn the mechanism of that increase and understand the nature of the messengers that move atoms during the coarsening process.

What Thiel and Evans are looking for is a general principle that explains what they call additive-enhanced coarsening. To do that, Thiel said they still need to collect and analyze data from more coarsening systems.

Evans said a better understanding of the coarsening process can help researchers develop small structures – including nanoscale technologies, catalysts or drug suspensions – that resist coarsening and are therefore more durable. A better understanding could also help researchers manipulate coarsening to develop structures with a very narrow distribution of particle sizes, something important to some nanotechnologies.

"When we're building something on a small scale, for it to be useful, it has to be robust, it has to survive," Evans said. "And one thing we're looking at is the stability of the very tiny structures that are crucial to nanoscale technologies."