Feb 2 2011

The same properties that make engineered nanoparticles attractive for numerous applications-small as a virus, biologically and environmentally stabile, and water-soluble - also cause concern about their long-term impacts on environmental health and safety (EHS). One particular characteristic, the tendency for nanoparticles to clump together in solution, is of great interest because the size of these clusters may be key to whether or not they are toxic to human cells.

Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have demonstrated for the first time a method for producing nanoparticle clusters in a variety of controlled sizes that are stable over time so that their effects on cells can be studied properly.*

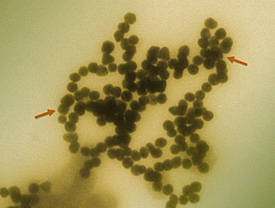

Transmission electron micrograph of gold nanoparticles clustering in solution. The distance between the two red arrows is approximately 280 nanometers, some 200 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. The individual nanoparticles are approximately 15 nanometers in diameter, about the distance across three side-by-side sodium atoms. Credit: A. Keene, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

Transmission electron micrograph of gold nanoparticles clustering in solution. The distance between the two red arrows is approximately 280 nanometers, some 200 times smaller than the diameter of a human hair. The individual nanoparticles are approximately 15 nanometers in diameter, about the distance across three side-by-side sodium atoms. Credit: A. Keene, U.S. Food and Drug Administration

In their tests, the NIST team made samples of gold, silver, cerium oxide and positively-charged polystyrene nanoparticles and suspended them separately in cell culture medium, allowing clumping to occur in each. They stopped the clumping by adding a protein, bovine serum albumin (BSA), to the mixtures. The longer the nanoparticles were allowed to clump together, the larger the size of the resulting cluster. For example, a range of clustering times using 23 nanometer silver nanoparticles produced a distribution of masses between 43 and 1,400 nanometers in diameter. Similar size distributions for the other three nanoparticle types were produced using this method.

The researchers learned that using the same "freezing times"-the points at which BSA was added to halt the process-yielded consistent size distributions for all four nanoparticle types. Additionally, all of the BSA-controlled dispersions remained stable for 2-3 days, which is sufficient for many toxicity studies.

Having successfully shown that they could control the production of nanoparticle clumps of different sizes, the researchers wanted next to prove that their creations could be put to work. Different-sized silver nanoparticle clusters were mixed with horse blood in an attempt to study the impact of clumping size on red blood cell toxicity. The presence of hemoglobin, the iron-based molecule in red blood cells that carries oxygen, would tell researchers if the cells had been lysed (broken open) by silver ions released into the solution from the clusters. In turn, measuring the amount of hemoglobin in solution for each cluster size would define the level of toxicity-possibly related to the level of silver ion release-for that specific average size.

What the researchers found was that red blood cell destruction decreased as cluster size increased. They hypothesize that large nanoparticle clusters dissolve more slowly than small ones, and therefore, release fewer silver ions into solution.

In the future, the NIST team plans to further characterize the different cluster sizes achievable through their production method, and then use those clusters to study the impact on cytotoxicity of coatings (such as polymers) applied to the nanoparticles.