In research appearing in today's issue of the journal Nature Nanotechnology, Nongjian "NJ" Tao, a researcher at the Biodesign Institute at Arizona State University, has demonstrated a clever way of controlling electrical conductance of a single molecule, by exploiting the molecule's mechanical properties.

Such control may eventually play a role in the design of ultra-tiny electrical gadgets, created to perform myriad useful tasks, from biological and chemical sensing to improving telecommunications and computer memory.

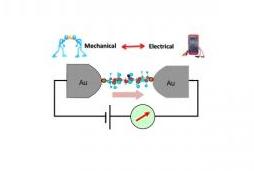

When electrical devices are shrunk to a molecular scale, both electrical and mechanical properties of a given molecule become critical. Specific properties may be exploited, depending on the needs of the application. Here, a single molecule is attached at either end to a pair of gold electrodes, forming an electrical circuit, whose current can be measured.

When electrical devices are shrunk to a molecular scale, both electrical and mechanical properties of a given molecule become critical. Specific properties may be exploited, depending on the needs of the application. Here, a single molecule is attached at either end to a pair of gold electrodes, forming an electrical circuit, whose current can be measured.

Tao leads a research team used to dealing with the challenges entailed in creating electrical devices of this size, where quirky effects of the quantum world often dominate device behavior. As Tao explains, one such issue is defining and controlling the electrical conductance of a single molecule, attached to a pair of gold electrodes.

"Some molecules have unusual electromechanical properties, which are unlike silicon-based materials. A molecule can also recognize other molecules via specific interactions." These unique properties can offer tremendous functional flexibility to designers of nanoscale devices.

In the current research, Tao examines the electromechanical properties of single molecules sandwiched between conducting electrodes. When a voltage is applied, a resulting flow of current can be measured. A particular type of molecule, known as pentaphenylene, was used and its electrical conductance examined.

Tao's group was able to vary the conductance by as much as an order of magnitude, simply by changing the orientation of the molecule with respect to the electrode surfaces. Specifically, the molecule's tilt angle was altered, with conductance rising as the distance separating the electrodes decreased, and reaching a maximum when the molecule was poised between the electrodes at 90 degrees.

The reason for the dramatic fluctuation in conductance has to do with the so-called pi orbitals of the electrons making up the molecules, and their interaction with electron orbitals in the attached electrodes. As Tao notes, pi orbitals may be thought of as electron clouds, protruding perpendicularly from either side of the plane of the molecule. When the tilt angle of a molecule trapped between two electrodes is altered, these pi orbitals can come in contact and blend with electron orbitals contained in the gold electrode—a process known as lateral coupling. This lateral coupling of orbitals has the effect of increasing conductance.

In the case of the pentaphenylene molecule, the lateral coupling effect was pronounced, with conductance levels increasing up to 10 times as the lateral coupling of orbitals came into greater play. In contrast, the tetraphenyl molecule used as a control for the experiments did not exhibit lateral coupling and conductance values remained constant, regardless of the tilt angle applied to the molecule. Tao says that molecules can now be designed to either exploit or minimize lateral coupling effects of orbitals, thereby permitting the fine-tuning of conductance properties, based on an application's specific requirements.

A further self-check on the conductance results was carried out using a modulation method. Here, the molecule's position was jiggled in 3 spatial directions and the conductance values observed. Only when these rapid perturbations specifically changed the tilt angle of the molecule relative to the electrode were conductance values altered, indicating that lateral coupling of electron orbitals was indeed responsible for the effect. Tao also suggests that this modulation technique may be broadly applied as a new method for evaluating conductance changes in molecular-scale systems.

Source: http://www.asu.edu/