A research team at the U.S. Department of Energy's Brookhaven National Laboratory have published a technique for studying exotic ferroelectric materials, revealing details on a sub-atomic level. The research could open up possibilities for compact, efficient devices based on a new generation of nanoelectronics.

Brookhaven scientists used a technique called electron holography to capture images of the electric fields created by the materials' atomic displacement with picometer precision - that's the trillionths-of-a-meter scale crucial to understanding these promising nanoparticles. By applying different levels of electricity and adjusting the temperature of the samples, researchers demonstrated a method for identifying and describing the behavior and stability of ferroelectrics at the smallest-ever scale, with major implications for data storage. The research has been published in Nature Materials.

Yimei Zhu (back) and Myung-geun Han - the primary researchers on the Brookhaven team, examine the breakthrough nanoscale images of ferroelectric polarizations.

Yimei Zhu (back) and Myung-geun Han - the primary researchers on the Brookhaven team, examine the breakthrough nanoscale images of ferroelectric polarizations.

"This kind of detail is just amazing - for the first time ever we can actually see the positions of atoms and link them to local ferroelectricity in nanoparticles," said Brookhaven physicist Yimei Zhu. "This kind of fundamental insight is not only a technical milestone, but it also opens up new engineering possibilities."

Ferroelectrics are perhaps best understood as the mysterious cousins of more familiar ferromagnetic materials, commonly seen in everything from refrigerator magnets to computer hard drives. As the name suggests, ferromagnetics have intrinsic magnetic dipole moments, meaning that they are always oriented toward either "north" or "south". These dipole moments tend to align themselves on larger scales, giving rise to the magnetization responsible for attraction and repulsion. Applying an external magnetic field can actually flip that magnetization, allowing programmers and engineers to manipulate the material.

Similarly, ferroelectric materials also have a molecular-scale dipole moment, but one characterized by a positive or negative electric charge rather than magnetic polarity. This polarization can also be manipulated, but flipping the charge requires an external electric field. This critical, tunable characteristic comes from an internal subatomic asymmetry and ordering phenomena, which was imaged in detail for the first time by the transmission electron microscopes used in this new study.

Current magnetic memory devices, such as the hard drives in most computers, "write" information into ferromagnetic materials by flipping that intrinsic dipole moment to correspond with the 1 or 0 of a computer's binary code. Those manipulated polarities then translate into everything from movies to web sites. The remarkable ability of these materials to retain information even when turned off - what's called nonvolatile storage - makes them an essential building block for our increasingly digital world.

|

Ferroelectric compounds are fascinating materials which have inherent electric dipole moments. This rare property is ideally suited for use in data storage, and could result in thumbnail-sized devices capable of storing terabytes of information.

Click here for more on ferroelectric materials from AZoNano.

|

In the emerging ferroelectric model of data storage, applying an electric field toggles between that material's two electric states, which translates into code. When scaled up similarly to ferromagnetics, that process can manifest on a computer as the writing or reading of digital information. And ferroelectric materials may trump their magnetic counterparts in ultimate efficacy.

"Ferroelectric materials can retain information on a much smaller scale and with higher density than ferromagnetics," Zhu said. "We're looking at moving from micrometers (millionths of a meter) down to nanometers (billionths of a meter). And that's what's really exciting, because we now know that on the nanoscale each particle can become its own bit of information. We knew very little about manipulating ferroelectric behavior in nanomaterials before this."

The trick to scaling up individual ferroelectric nanoparticles into useful devices is understanding just how tightly together they can be packed and ordered without compromising their distinct polarizations, which theory suggests should be extremely difficult to achieve. The electron holography experiments conducted at Brookhaven Lab demonstrated a method for determining those parameters under a range of conditions.

"Electron holography is an interferometry technique using coherent electron waves," said Brookhaven physicist Myung-Geun Han. "When electron waves pass through a ferroelectric sample, they are influenced by local electric fields, yielding a so-called phase-shift. The interference pattern between the electrons that pass through electric fields and those that don't creates what's called an electron hologram, which allows us to directly 'see' those local electric fields around individual ferroelectric nanoparticles."

|

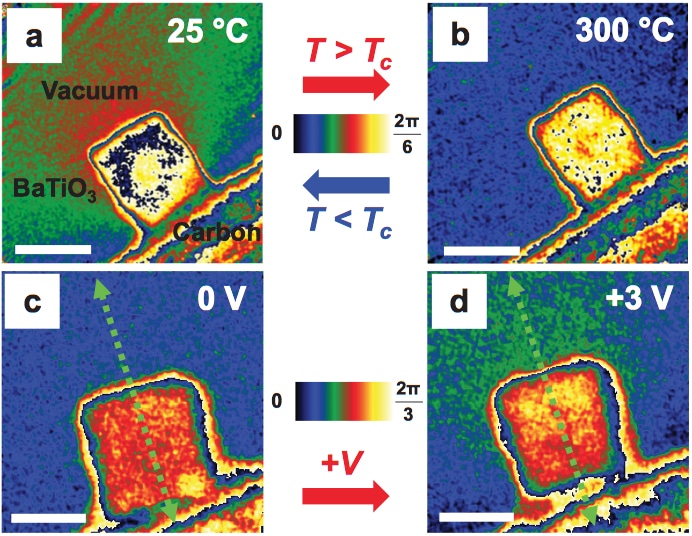

| Direct polarization images of individual ferroelectric nano cubes captured with electron holography. The fringing field, or “footprint” of electric polarization, can be seen clearly in (a), but it vanishes when the material is subjected to high temperatures (b). The lower images show that no fringing field can be observed before application of electricity (c), but a clear field emanates after current is applied (d). |

Local electric fields emanate from ferroelectric nanoparticles, and these "fringing" fields are like the functional footprint of a particle's polarity. Consider the way a small magnet's effects can be felt even at a slight distance from its surface - a similar field exists in ferroelectric materials. When imaged by electron holography, the fringing field indicates the integrity of electrical polarity and the distance required between particles before they begin to interfere with each other.

The study revealed that the electric polarity could remain stable for individual ferroelectric materials, meaning that each nanoparticle can be used as a data bit. But because of their fringing fields, ferroelectrics need a little elbow room (on the order of five nanometers) to effectively operate. Otherwise, once scaled up for computer storage, they can't keep code intact and the information becomes garbled and corrupted. Understanding the atomic-scale properties revealed in this study will help guide implementation of these exotic particles.

"Properly used, ferroelectrics could ramp up memory density and store an unparalleled multiple terabytes of information on just one square inch of electronics," Han said. "This brings us closer to engineering such devices."

The ferroelectric nanoparticles tested, semiconducting germanium telluride and insulating barium titanate, were engineered at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and brought to Brookhaven Lab for the electron holography experiments. Additional experiments using x-ray diffraction were conducted at Argonne National Laboratory's Advanced Photon Source.

The work featured collaborators from the University of California at Berkeley, the University of New Orleans, Central Michigan University, Lawrence Berkeley National Lab and Brookhaven National Lab. In addition to Zhu and Han, Brookhaven scientist Vyacheslav Volkov was also involved in the project. The research was funded by DOE's Office of Science.