Jul 4 2013

A process combining some comparatively cheap materials and the same antifreeze that keeps an automobile radiator from freezing in cold weather may be the key to making solar cells that cost less and avoid toxic compounds, while further expanding the use of solar energy.

And when perfected, this approach might also cook up the solar cells in a microwave oven similar to the one in most kitchens.

Engineers at Oregon State University have determined that ethylene glycol, commonly used in antifreeze products, can be a low-cost solvent that functions well in a “continuous flow” reactor – an approach to making thin-film solar cells that is easily scaled up for mass production at industrial levels.

The research, just published in Material Letters, a professional journal, also concluded this approach will work with CZTS, or copper zinc tin sulfide, a compound of significant interest for solar cells due to its excellent optical properties and the fact these materials are cheap and environmentally benign.

“The global use of solar energy may be held back if the materials we use to produce solar cells are too expensive or require the use of toxic chemicals in production,” said Greg Herman, an associate professor in the OSU School of Chemical, Biological and Environmental Engineering. “We need technologies that use abundant, inexpensive materials, preferably ones that can be mined in the U.S. This process offers that.”

By contrast, many solar cells today are made with CIGS, or copper indium gallium diselenide. Indium is comparatively rare and costly, and mostly produced in China. Last year, the prices of indium and gallium used in CIGS solar cells were about 275 times higher than the zinc used in CZTS cells.

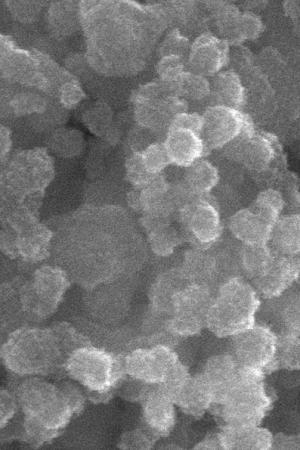

The technology being developed at OSU uses ethylene glycol in meso-fluidic reactors that can offer precise control of temperature, reaction time, and mass transport to yield better crystalline quality and high uniformity of the nanoparticles that comprise the solar cell – all factors which improve quality control and performance.

This approach is also faster – many companies still use “batch mode” synthesis to produce CIGS nanoparticles, a process that can ultimately take up to a full day, compared to about half an hour with a continuous flow reactor. The additional speed of such reactors will further reduce final costs.

“For large-scale industrial production, all of these factors – cost of materials, speed, quality control – can translate into money,” Herman said. “The approach we’re using should provide high-quality solar cells at a lower cost.”

The performance of CZTS cells right now is lower than that of CIGS, researchers say, but with further research on the use of dopants and additional optimization it should be possible to create solar cell efficiency that is comparable.

This project is one result of work through the Center for Sustainable Materials Chemistry, a collaborative effort of OSU and five other academic institutions, supported by the National Science Foundation. Funding was provided by Sharp Laboratories of America. The goal is to develop materials and products that are safe, affordable and avoid the use of toxic chemicals or expensive compounds.