Jun 11 2014

Researchers at Sandia National Laboratories, along with collaborators from Rice University and the Tokyo Institute of Technology, are developing new terahertz detectors based on carbon nanotubes that could lead to significant improvements in medical imaging, airport passenger screening, food inspection and other applications.

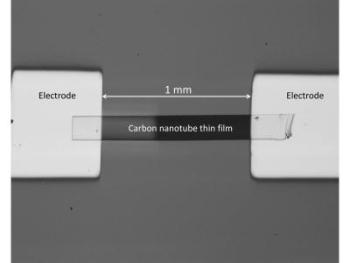

This photograph depicts the terahertz detector developed by researchers at Sandia National Laboratories, Rice University and the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The terahertz radiation is captured by a carbon nanotube thin film contacted by two gold electrodes. Credit: Rice University

This photograph depicts the terahertz detector developed by researchers at Sandia National Laboratories, Rice University and the Tokyo Institute of Technology. The terahertz radiation is captured by a carbon nanotube thin film contacted by two gold electrodes. Credit: Rice University

A paper in Nano Letters journal, "Carbon Nanotube Terahertz Detector," debuted in the May 29 edition of the publication's "Just Accepted Manuscripts" section. The paper describes a technique that uses carbon nanotubes to detect light in the terahertz frequency range without cooling.

Historically, the terahertz frequency range — which falls between the more conventional ranges used for electronics on one end and optics on another — has presented great promise along with vexing challenges for researchers, said Sandia's François Léonard, one of the authors.

"The photonic energy in the terahertz range is much smaller than for visible light, and we simply don't have a lot of materials to absorb that light efficiently and convert it into an electronic signal," said Léonard. "So we need to look for other approaches."

Terahertz technology offers hope in medicine and other applications

Researchers need to solve this technical problem to take advantage of the many beneficial applications for terahertz radiation, said co-author Junichiro Kono of Rice University. Terahertz waves, for example, can easily penetrate fabric and other materials and could provide less intrusive ways for security screenings of people and cargo. Terahertz imaging could also be used in food inspection without adversely impacting food quality.

Perhaps the most exciting application offered by terahertz technology, said Kono, is as a potential replacement for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) technology in screening for cancer and other diseases.

"The potential improvements in size, ease, cost and mobility of a terahertz-based detector are phenomenal," he said. "With this technology, you could conceivably design a hand-held terahertz detection camera that images tumors in real-time, with pinpoint accuracy. And it could be done without the intimidating nature of MRI technology."

Carbon nanotubes may help bridge the technical gap

Sandia, its collaborators and Léonard, in particular, have been studying carbon nanotubes and related nanomaterials for years. In 2008, Léonard authored The Physics of Carbon Nanotube Devices, which looks at the experimental and theoretical aspects of carbon nanotube devices.

Carbon nanotubes are long, thin cylinders composed entirely of carbon atoms. While their diameters are in the 1- to 10-nanometer range, they can be up to several centimeters long. The carbon-carbon bond is very strong, so it resists any kind of deformation.

The scientific community has long been interested in the terahertz properties of carbon nanotubes, said Léonard, but virtually all of the research to date has been theoretical or computer-model based. A handful of papers have investigated terahertz sensing using carbon nanotubes, but those have focused mainly on the use of a single or single bundle of nanotubes.

The problem, Léonard said, is that terahertz radiation typically requires an antenna to achieve coupling into a single nanotube due to the relatively large size of terahertz waves. The Sandia, Rice University and Tokyo Institute of Technology research team, however, found a way to create a small but visible-to-the-naked eye detector, developed by Rice researcher Robert Hauge and graduate student Xiaowei He, that uses carbon nanotube thin films without requiring an antenna. The technique is thus amenable to simple fabrication and represents one of the team's most important achievements, Léonard said.

"Carbon nanotube thin films are extremely good absorbers of electromagnetic light," he explained. In the terahertz range, it turns out that thin films of these nanotubes will soak up all of the incoming terahertz radiation. Nanotube films have even been called "the blackest material" for their ability to absorb light effectively.

The researchers were able to wrap together several nanoscopic-sized tubes to create a macroscopic thin film that contains a mix of metallic and semiconducting carbon nanotubes.

"Trying to do that with a different kind of material would be nearly impossible, since a semiconductor and a metal couldn't coexist at the nanoscale at high density," explained Kono. "But that's what we've achieved with the carbon nanotubes."

The technique is key, he said, because it combines the superb terahertz absorption properties of the metallic nanotubes and the unique electronic properties of the semiconducting carbon nanotubes. This allows researchers to achieve a photodetector that does not require power to operate, with performance comparable to existing technology.

A clear path to performance improvement

The next step for researchers, Léonard said, is to improve the design, engineering and performance of the terahertz detector.

For instance, they need to integrate an independent terahertz radiation source with the detector for applications that require a source, Léonard said. The team also needs to incorporate electronics into the system and to further improve properties of the carbon nanotube material.

"We have some very clear ideas about how we can achieve these technical goals," said Léonard, adding that new collaborations with industry or government agencies are welcome.

"Our technical accomplishments open up a new path for terahertz technology, and I am particularly proud of the multidisciplinary and collaborative nature of this work across three institutions," he said.

In addition to Sandia, Rice and Tokyo Tech, the project received contributions from researchers taking part in NanoJapan, a 12-week summer program that enables freshman and sophomore physics and engineering students from U.S. universities to complete nanoscience research internships in Japan focused on terahertz nanoscience.