The light-warping structures known as metamaterials have a new trick in their ever-expanding repertoire. Researchers at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) have built a silver, glass and chromium nanostructure that can all but stop visible light cold in one direction while giving it a pass in the other.* The device could someday play a role in optical information processing and in novel biosensing devices.

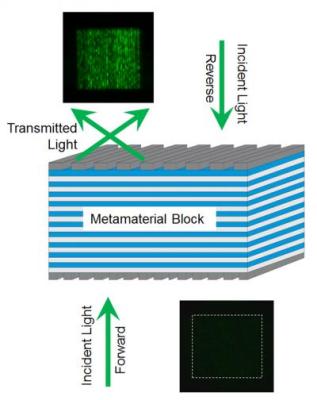

This is a schematic of NIST's one-way metamaterial. Forward traveling green light (left) or red light passes through the multilayered block and comes out at an angle due to diffraction off of grates on the surface of the material. Light traveling in the opposite direction (right) is almost completely filtered by the metamaterial and can't pass through. Credit: Xu/NIST

This is a schematic of NIST's one-way metamaterial. Forward traveling green light (left) or red light passes through the multilayered block and comes out at an angle due to diffraction off of grates on the surface of the material. Light traveling in the opposite direction (right) is almost completely filtered by the metamaterial and can't pass through. Credit: Xu/NIST

In recent years, scientists have designed nanostructured materials that allow microwave or infrared light to propagate in only one direction. Such structures hold potential for applications in optical communication—for instance, they could be integrated into photonic chips that split or combine signals carried by light waves. But, until now, no one had achieved one-way transmission of visible light, because existing devices could not be fabricated at scales small enough to manipulate visible light's short wavelengths. (So-called "one-way mirrors" don't really do this—they play tricks with relative light levels.)

To get around that roadblock, NIST researchers Ting Xu and Henri Lezec combined two light-manipulating nanostructures: a multi-layered block of alternating silver and glass sheets and metal grates with very narrow spacings.

The silver-glass structure is an example of a "hyperbolic" metamaterial, which treats light differently depending on which direction the waves are traveling. Because the structure's layers are only tens of nanometers thick—much thinner than visible light's 400 to 700 nanometer wavelengths—the block is opaque to visible light coming in from outside. Light can, however, propagate inside the material within a narrow range of angles.

Xu and Lezec used thin-film deposition techniques at the NIST NanoFab user facility to build a hyperbolic metamaterial block.Guided by computer simulations, they fabricated the block out of 20 extremely thin alternating layers of silicon dioxide glass and silver. To coax external light into the layered material, the researchers added to the block a set of chromium grates with narrow, sub-wavelength spacings chosen to bend incoming red or green light waves just enough to propagate inside the block. On the other side of the block, the researchers added another set of grates to kick light back out of the structure, although angled away from its original direction.

While the second set of grates let light escape the material, their spacing was slightly different from that of the first grates. As a result, the reverse-direction grates bent incoming light either too much or not enough to propagate inside the silver-glass layers. Testing their structures, the researchers found that around 30 times more light passed through in the forward direction than in reverse, a contrast larger than any other achieved thus far with visible light.

Combining materials that could be made using existing methods was the key to achieving one-way transmission of visible light, Lezec says. Without the intervening silver-and-glass blocks, the grates would have needed to be fabricated and aligned more precisely than is possible with current techniques. "This three-step process actually relaxes the fabrication constraints," Lezec says.

In the future, the new structure could be integrated into photonic chips that process information with light instead of electricity. Lezec thinks the device also could be used to detect tiny particles for biosensing applications. Like the chrome grates, nanoscale particles also can deflect light to angles steep enough to travel through the hyperbolic material and come out the other side, where the light would be collected by a detector. Xu has run simulations suggesting such a scheme could provide high-contrast particle detection and is hoping to test the idea soon. "I think it's a cool device where you would be able to sense the presence of a very small particle on the surface through a dramatic change in light transmission," says Lezec.

*T. Xu and H.J. Lezec. Visible-frequency asymmetric transmission devices incorporating a hyperbolic metamaterial. Nature Communications. 2014, 5, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5141. http://www.nature.com/ncomms/2014/140617/ncomms5141/full/ncomms5141.html