Aug 27 2014

By combining plasmonics and optical microresonators, researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have created a new optical amplifier (or laser) design, paving the way for power-on-a-chip applications.

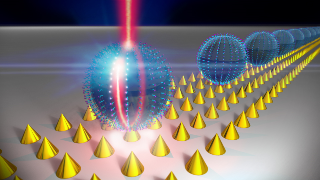

Hybrid optoplasmonic system showing the operation of amplification. (Image credit: Nathan Bajandas, Beckman ITG)

Hybrid optoplasmonic system showing the operation of amplification. (Image credit: Nathan Bajandas, Beckman ITG)

“We have made optical systems at the microscopic scale that amplify light and produce ultra-narrowband spectral output,” explained J. Gary Eden, a professor of electrical and computer engineering (ECE) at Illinois. “These new optical amplifiers are well-suited for routing optical power on a chip containing both electronic and optical components.

“Their potential applications in medicine are exciting because the amplifiers are actuated (‘pumped’) by light that is able to pass through human skin. For this reason, these microsphere-based amplifiers are able to transmit signals from cells and buried biomedical sensors to electrical and optical networks outside the body.”

The speed of currently available semiconductor electronics is limited to about 10 GHz due to heat generation and interconnects delay time issues. Though, not limited by speed, dielectric-based photonics are limited in size by the fundamental laws of diffraction. The researchers, led by Eden and ECE associate professor Logan Liu, found that plasmonics—metal nanostructures—can serve as a bridge between photonics and nanoelectronics, to combine the size of nanoelectronics and the speed of dielectric photonics.

“We have demonstrated a novel optoplasmonic system comprising plasmonic nanoantennas and optical microcavities capable of active nanoscale field modulation, frequency switching, and amplification of signals,” states Manas Ranjan Gartia, lead author of the article, "Injection- Seeded Optoplasmonic Amplifier in the Visible," published in the journal Scientific Reports. “This is an important step forward for monolithically building on-chip light sources inside future chips that can use much less energy while providing superior speed performance of the chips.”

At the heart of the amplifier is a microsphere (made of polystyrene or glass) that is approximately 10 microns in diameter. When activated by an intense beam of light, the sphere generates internally a narrowband optical signal that is produced by a process known as Raman scattering. Molecules tethered to the surface of the sphere by a protein amplify the Raman signal, and in concert with a nano-structured surface in contact to the sphere, the amplifier produces visible (red or green) light having a bandwidth that matches the internally-generated signal.

The proposed design is well-suited for routing narrowband optical power on-a-chip. Over the past five decades, optical oscillators and amplifiers have typically been based on the buildup of the field from the spontaneous emission background. Doing so limits the temporal coherence of the output, lengthens the time required for the optical field to grow from the noise, and often is responsible for complex, multiline spectra.

“In our design, we use Raman assisted injection-seeded locking to overcome the above problems. In addition to the spectral control afforded by injection-locking, the effective Q of the amplifier can be specified by the bandwidth of the injected Raman signal,” Gartia said. This characteristic contrasts with previous WGM-based lasers and amplifiers for which the Q is determined solely by the WGM resonator.

In addition to Eden, Liu, and Gartia, co-authors of the paper include Sujin Seo, Junhwan Kim, Te-Wei Chang, Assistant Professor Gaurav Bahl from Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering, and Prof. Meng Lu, ECE alumnus and currently assistant professor at Iowa State University. The research was done at Micro and Nanotechnology Laboratory at Illinois.