Complex oxides have long tantalized the materials science community for their promise in next-generation energy and information technologies. Complex oxide crystals combine oxygen atoms with assorted metals to produce unusual and very desirable properties. Because their electrons interact strongly with their environments, complex oxides are versatile, existing as insulators, metals, magnets, and superconductors. They can tightly couple diverse physical properties, such as stress and strain, magnetism and magnetic order, electric field and polarization.

Collaborators from Korea, Norway, Ukraine and the United States analyzed atomic-scale polarization behavior and chemical composition for a ferroelectric (BFO) film on a metal (LSMO) to reveal electrically driven chemical changes that may someday be manipu

Collaborators from Korea, Norway, Ukraine and the United States analyzed atomic-scale polarization behavior and chemical composition for a ferroelectric (BFO) film on a metal (LSMO) to reveal electrically driven chemical changes that may someday be manipu

“In highly correlated electron systems, physical properties are interconnected like a tangle of strings,” said Albina Borisevich of the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory. “You don’t always know what will happen when you pull on one string. Often one string takes others with it.”

Borisevich led a project that made a surprising discovery—that intrinsic electric fields can drive oxygen diffusion at interfaces in engineered thin films made of complex oxides. The study is published in the September issue of Nature Materials.

Increased understanding of the properties of complex oxides will improve the ability to predict and control materials for new energy technologies. Researchers can custom-build complex oxides to pull on specific strings by changing an oxide’s chemical composition or layering it with metals or insulators. These novel materials may exhibit magnetic, electrical and mechanical properties, alone or in combination, that enable feats not possible today, such as electric-field-based data storage that is more energy-efficient than today’s magnetic memory or more efficient fuel cells that alter the concentration of charged atoms, or ions, at sites of key chemical reactions.

“Add more metal types and you’ve added more functionality. But you’ve also added more complexity,” Borisevich said. “At the interface between two materials, complexity goes through the roof.”

Collaborating to conquer complexity

The surprising discovery that intrinsic electric fields can drive oxygen diffusion at interfaces of complex oxides may serve as a basis for design of new electronic devices utilizing both electrons and ions.

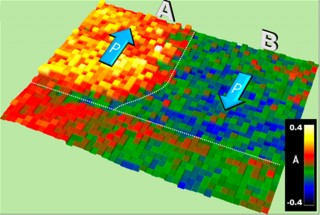

The researchers, from Korea, Norway, Ukraine and the United States, observed the effect in ferroelectrics, materials that exhibit switchable electrical polarization, or asymmetric distribution of positive and negative electrical charges. Ferroelectrics usually have regions, or domains, that can be as small as several nanometers, with different directions of polarization. Their properties are used in some memory devices, where domains with positive and negative polarization serve as “bits” that encode information. However, the longevity of these devices and the power required to “write” information is determined by what is happening at interfaces between the positively or negatively polarized ferroelectric domains and their metallic substrates.

The researchers examined metal–ferroelectric interfaces for positively and negatively polarized domains. Their major finding was that, depending on the charge, either purely electrical or combined electrical and chemical phenomena were at play.

When a ferroelectric is joined with another material, polarization causes charges to accumulate at the interface. This excess charge is called “polarization charge.” The collaborators found that the interface of the ferroelectric material behaved differently depending on the sign of the polarization charge (positive or negative).

At the interface with positive polarization charge, negatively charged electrons were syphoned in from the metal to attenuate it. Surprisingly, for negative polarization charge, the opposite did not happen—that is, electrons were not pushed out of the interface region. Instead, negatively charged oxygen ions left, creating defects called oxygen vacancies.

“With the change of polarization charge, not only the sign but the physical nature of the compensating chemical species changes,” said Borisevich, who works in ORNL’s Materials Science and Technology Division. “Charge compensation by oxygen vacancies highlights the important role of ionic phenomena in oxide electronics and opens a pathway for new device concepts.” For example, someday engineers may design devices in which ions manipulate electrical response or vice versa.

Two compensatory mechanisms

On a substrate of strontium titanate (SrTiO3), the researchers layered a metallic oxide called lanthanum strontium manganite, or (La0.67Sr0.33)MnO3 (LSMO), an electrical contact providing a reservoir of electrons. Atop the metal layers they added layers of an insulator, a ferroelectric material called bismuth ferrite, or BiFeO3 (BFO).

To explore electronic and chemical effects induced by ferroelectric polarization at the interface of the metal and the insulator, the researchers coupled two techniques. First, aberration-corrected scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) mapped, at the atomic level, polarization changes throughout the ferroelectric material and its interface with the metal. It demonstrated structural distortions at the interface between the ferroelectric material and the metal on the side of the material with negative polarization charge but not on the side with positive charge.

Second, electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS), which provides chemical information, indicated sites of oxygen-atom depletion and oxidation-state changes of iron and manganese metals. This tool allowed the researchers to track the decrease in oxygen concentration occurring at the interface with negative polarization charge. It also demonstrated that the valence state, which gives an atom power to combine with other atoms, was different in the metal manganese at the two different interfaces. The experimental observations coupled with theoretical results built a strong case for oxygen vacancy compensation of charge for the side of the material with negative polarization and electronic compensation for the positive side.

The exact nature of the compensating species at ferroelectric interfaces can have a significant effect on switching behavior because not only electrons but also ions need to move at the interface when the polarization charge is switched. The study therefore suggests a promising role for electrochemical phenomena at oxide interfaces, opening possibilities for fine-tuning switching by engineering local oxygen concentration.

Said Borisevich, “In the future, we want to move beyond tracking different aspects of interface properties at the atomic scale and toward coming up with a desired static and/or dynamic behavior and then making it happen at the intersection of electronic and chemical/electrochemical phenomena characteristic of these systems.”

The title of the study is “Direct observation of ferroelectric field effect and vacancy-controlled screening at the BiFeO3/LaxSr1–xMnO3 interface.” Young-Min Kim of the Korea Basic Science Institute did imaging and spectroscopy at ORNL, conducting STEM/EELS study and data analysis; Anna Morozovska and Eugene Eliseev of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine did device-level modeling, Mark Oxley of Vanderbilt University did EELS profile simulations; Rohan Mishra of Vanderbilt University, who is a visiting scientist at ORNL, and S. T. Pantelides, who holds joint appointments at Vanderbilt and ORNL, conducted first principles calculations; Sverre Selbach and Tor Grande of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology provided solid-state chemistry reasoning; and Sergei Kalinin of ORNL and the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences and Albina Borisevich of ORNL conceived and directed the project.

DOE’s Office of Science, the National Science Foundation and the State Fund of Fundamental Research of Ukraine sponsored the research. The work was conducted in part at the Center for Nanophase Materials Sciences and the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center, DOE Office of Science User Facilities at ORNL and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, respectively.

UT-Battelle manages ORNL for DOE’s Office of Science. The single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, the Office of Science is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time.—by Dawn Levy