Feb 20 2015

It’s nearly 50 years since Gordon Moore predicted that the density of transistors on an integrated circuit would double every two years. “Moore’s Law” has turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy that technologists pushed to meet, but to continue into the future, engineers will have to make radical changes to the structure or composition of circuits. One potential way to achieve this is to develop devices based on single-molecule connections.

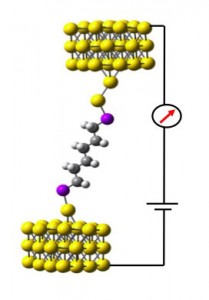

A hexane (six-carbon) molecule between two gold electrodes. A new UC Davis technique gives better measurements of these circuits. (Josh Hihath/UC Davis)

A hexane (six-carbon) molecule between two gold electrodes. A new UC Davis technique gives better measurements of these circuits. (Josh Hihath/UC Davis)

New work by Josh Hihath’s group at the UC Davis Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, published Feb. 16 in the journal Nature Materials, could help technologists make that jump. Hihath’s laboratory has developed a method to measure the conformation of single molecule “wiring,” resolving a clash between theoretical predictions and experiments.

“We’re trying to make transistors and diodes out of single molecules, and unfortunately you can’t currently control exactly how the molecule contacts the electrode or what the exact configuration is,” Hihath said. “This new technique gives us a better measurement of the configuration, which will provide important information for theoretical modeling.”

Until now, there has been a wide gap between the predicted electrical behavior of single molecules and experimental measurements, with results being off by as much as ten-fold, Hihath said.

Hihath’s experiment uses a layer of alkanes (short chains of carbon atoms, such as hexane, octane or decane) with either sulfur or nitrogen atoms on each end that allow them to bind to a gold substrate that acts as one electrode. The researchers then bring the gold tip of a Scanning Tunneling Microscope towards the surface to form a connection with the molecules. As the tip is then pulled away, the connection will eventually consist of a single-molecule junction that contains six to ten carbon atoms (depending on the molecule studied at the time).

By vibrating the tip of the STM while measuring electrical current across the junction, Hihath and colleagues were able to extract information about the configuration of the molecules.

“This technique gives us information about both the electrical and mechanical properties of the system and tells us what the most probable configuration is, something that was not possible before,” Hihath said.

The researchers hope the technique can be used to make better predictions of how molecule-scale circuits behave and design better experiments.

Coauthors on the paper are graduate students Habid Rascón-Ramos and Yuanhui Li and postdoctoral researcher Juan Manuel Artés, all at UC Davis. The work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the RISE program of the UC Davis Office of Research.