Mar 9 2015

Pick up a handful of sand, and it flows through your fingers like a liquid. But when you walk on the beach, the sand supports your weight like a solid. What happens to the forces between the jumbled sand grains when you step on them to keep you from sinking?

An international team of researchers collaborating at Duke University have developed a new way to measure the forces inside materials such as sand, soil or snow under pressure.

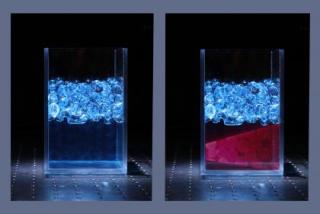

Researchers have developed a new way to measure the forces inside materials such as sand, soil or snow under pressure. Using a solution of hundreds of translucent hydrogel beads in a Plexiglass box to simulate soil, sand or snow, the technique relies on lasers coupled with force sensors, cameras and advanced computer algorithms to measure the forces between neighboring particles in 3-D. Photo by Felice Frankel and Joshua Dijksman.

Researchers have developed a new way to measure the forces inside materials such as sand, soil or snow under pressure. Using a solution of hundreds of translucent hydrogel beads in a Plexiglass box to simulate soil, sand or snow, the technique relies on lasers coupled with force sensors, cameras and advanced computer algorithms to measure the forces between neighboring particles in 3-D. Photo by Felice Frankel and Joshua Dijksman.

Described in the March 5 issue of Nature Communications, the technique uses lasers coupled with force sensors, digital cameras and advanced computer algorithms to peer inside and measure the forces between neighboring particles in 3-D.

The new approach will allow researchers to better understand phenomena like the jamming of grain hoppers or the early warning signs of earthquakes and avalanches, said study co-author Nicolas Brodu, now at the French institute Inria.

Whether footprints in sand, or the force of gravity on a mountain slope, physicists have long sought to understand what happens inside granular materials as they’re pressed, pushed or squeezed.

For centuries this simple question has been surprisingly difficult to answer. But more recently, thanks to advances in 3-D imaging techniques and the number-crunching power of computers, researchers are starting to get a better picture of what happens when granular materials like soil or snow are pushed together.

Brodu, along with physicists Robert Behringer of Duke University and Joshua Dijksman of Wageningen University in the Netherlands, describe how they use simple tools to measure the network of forces at it spreads from one particle to the next.

The researchers use a solution of hundreds of translucent hydrogel beads in a Plexiglass box to simulate materials like soil, sand or snow.

Anatomy of an Avalanche {Duke University Research}

A piston repeatedly pushes down on the beads in the box while a sheet of laser light scans the box, and a camera takes a series of cross-sectional images of the illuminated sections.

Like MRI scans used in medicine, the technique works by converting these cross-sectional “slices” into a 3-D image.

Custom-built imaging software stacks the hundreds of thousands of 2-D images together to reconstruct the surface of each individual particle in three dimensions, over time. By measuring the tiny deformations in the particles as they are squeezed together, the researchers are able to calculate the forces between them.

The new approach will help researchers better understand a range of natural and manmade hazards, such as why farmworkers stepping into grain bins sometimes experience a quicksand effect and are suddenly sucked under.

“This gives us hope of understanding what happens in disasters like a landslide, when packed soil and rocks on a mountain become loose and slide down,” Brodu said. “First it acts like a solid, and then for reasons physicists don’t completely understand, all of a sudden it destabilizes and starts to flow like a liquid. This transition from solid to liquid can only be understood if you know what’s going on inside the soil.”

The team has already used results from their technique to create a new model for the way particulate matter behaves, which is concurrently published in the journal Physical Review E.

This research was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (DMR1206351, DMS1248071), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NNX10AU01G), and the U.S. Army Research Office (W911NF-1-11-0110).