Aug 5 2016

A team of University of Pennsylvania researchers has developed a computer model that will aid in the design of nanocarriers, microscopic structures used to guide drugs to their targets in the body.

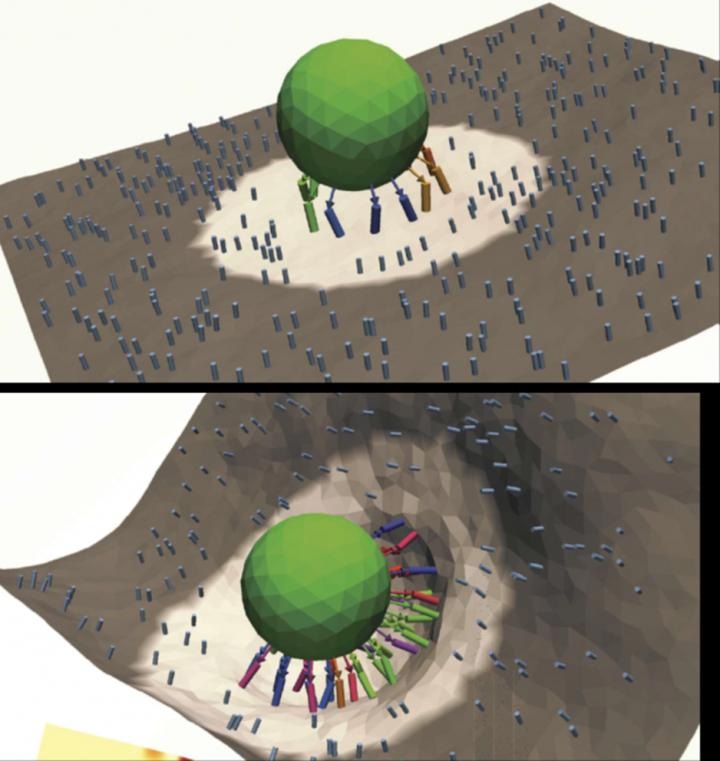

Previous work by some of the researchers uncovered a counter-intuitive relationship that suggested that adding more targeting molecules on the nanocarrier's surface is not always better, as increases in stability may come with decreases in targeting specificity. Understanding the role the fluttering of the target cell's surface plays in this equation is necessary for better design of nanocarriers. Credit: University of Pennsylvania

Previous work by some of the researchers uncovered a counter-intuitive relationship that suggested that adding more targeting molecules on the nanocarrier's surface is not always better, as increases in stability may come with decreases in targeting specificity. Understanding the role the fluttering of the target cell's surface plays in this equation is necessary for better design of nanocarriers. Credit: University of Pennsylvania

The model better accounts for how the surfaces of different types of cells undulate due to thermal fluctuations, informing features of the nanocarriers that will help them stick to cells long enough to deliver their payloads.

The study was led by Ravi Radhakrishnan, a professor in the departments of bioengineering and chemical and biomolecular engineering in Penn's School of Engineering and Applied Science, and Ramakrishnan Natesan, a member of his lab.

Also contributing to the study were Richard Tourdot, a Radhakrishnan lab member; David Eckmann, the Horatio C. Wood Professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care in Penn's Perelman School of Medicine; Portonovo Ayyaswamy, the Asa Whitney Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Applied Mechanics in Penn Engineering; and Vladimir Muzykantov, a professor of pharmacology in Penn Medicine.

It was published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

Nanocarriers can be designed with molecules on their exteriors that only bind to biomarkers found on a certain type of cell. This type of targeting could reduce side effects, such as when chemotherapy drugs destroy healthy cells instead of cancerous ones, but the biomechanics of this binding process are complex.

Previous work by some of the researchers uncovered a counter-intuitive relationship that suggested that adding more targeting molecules on the nanocarrier's surface is not always better.

A nanocarrier with more of those targeting molecules might find and bind to many of the corresponding biomarkers at once. While such a configuration is stable, it can decrease the nanocarrier's ability to distinguish between healthy and diseased tissues. Having fewer targeting molecules makes the nanocarrier more selective, as it will have a harder time binding to healthy tissue where the corresponding biomarkers are not over-expressed.

The team's new study adds new dimensions to the model of the interplay between the cellular surface and the nanocarrier.

"The cell surface itself is like a caravan tent on a windy day on a desert," Radhakrishnan said. "The more excess in the cloth, the more the flutter of the tent. Similarly, the more excess cell membrane area on the 'tent poles,' the cytoskeleton of the cell, the more the flutter of the membrane due to thermal motion."

The Penn team found that different cell types have differing amounts of this excess membrane area and that this mechanical parameter governs how well nanocarriers can bind to the cell. Accounting for the fluttering of the membrane in their computer models, in addition to the quantity of targeting molecules on the nanocarrier and biomarkers on the cell surface, has highlighted the importance of these mechanical aspects in how efficiently nanocarriers can deliver their payloads.

"These design criteria," Radhakrishnan said, "can be utilized in custom designing nanocarriers for a given patient or patient-cohort, hence showing an important way forward for custom nanocarrier design in the era of personalized medicine."