Aug 24 2016

A prototype part of the software system to manage data from the Square Kilometre Array (SKA) telescope has run on the world’s second fastest supercomputer in China.

The complete system, currently being designed by an international consortium, will process raw observations of distant stars and galaxies and turn them into a form that can be analysed by astronomers around the world.

It is known as the SKA Science Data Processor, or the ‘brain’ of the telescope.

Professor Andreas Wicenec, head of data intensive astronomy at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR)

The successful deployment of the prototype science data processor execution framework on the Tianhe-2 supercomputer was conducted by an international team led by Professor Tao An from Shanghai Astronomical Observatory in China and Professor Wicenec in Western Australia.

The execution framework provides the control and monitoring environment to execute millions of tasks, consuming and producing millions of data items on many thousands of individual computers.

This is the scale of processing required for every single SKA observation obtained within six to 12 hours.

Professor Wicenec said the novel execution framework of the science data processor is “data activated”, meaning individual data items are wrapped in an active piece of software that automatically triggers the applications needed to process it.

Whenever a data item is ready, that’s triggering the next task—the task is not running idle, waiting for anything.

Professor Andreas Wicenec, head of data intensive astronomy at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR)

Professor Tao An from Shanghai Astronomical Observatory said the prototype was initially run on 500 compute nodes of the supercomputer and then extended to 1000 nodes.

“The next step is to ramp up the number of individual items we’re deploying and then increase the number of computer nodes to what we are expecting for the SKA computer, which is about 8500,” he said.

Professor Wicenec said the system is now running 66,000 items and the next stage will be a few million.

“Then we’ll run between 50 and 60 million items on 8500 or 10,000 nodes,” he said.

Tianhe-2 was deployed on National Super Computing Center in Guangzhou, China, which has 16,000 computer nodes and can perform quadrillions of calculations per second.

It was the world’s fastest supercomputer from June 2013 until June 2016.

The most important part is the co-design and co-optimisation of SKA data processing software set and supercomputers such as Tianhe-2, preparing for the faster computers in a few years from now.

Professor Yutong Lu, Tianhe-2 director

This work was carried out as part of the Science Data Processor work package for the SKA, which is led by the University of Cambridge.

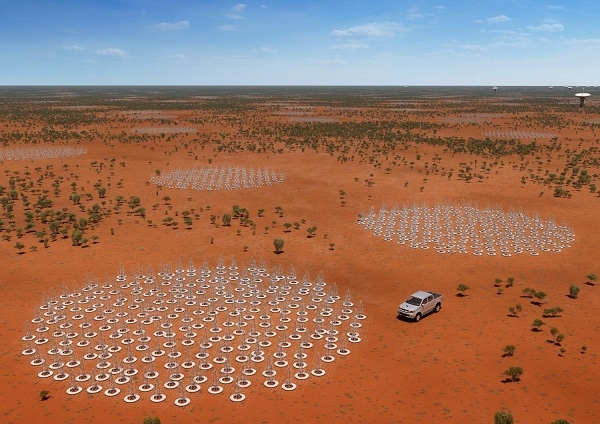

The SKA is arguably the world’s largest science project, with the low frequency part of the telescope alone set to have more than a quarter of a million antennas facing the sky.

Each of the two SKA telescopes will produce enough data to fill a typical laptop hard drive every second.

More Information:

The International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research (ICRAR) is a joint venture between Curtin University and The University of Western Australia with support and funding from the State Government of Western Australia.

ICRAR’s Data Intensive Astronomy team is leading the international effort to address the challenges surrounding the flow of data within the SKA observatory.

The Square Kilometre Array (SKA) project is an international effort to build the world’s largest radio telescope, led by the SKA Organisation based at the Jodrell Bank Observatory near Manchester. The SKA will conduct transformational science to improve our understanding of the Universe and the laws of fundamental physics, monitoring the sky in unprecedented detail and mapping it hundreds of times faster than any current facility.

The SKA is not a single telescope, but a collection of telescopes or instruments, called an array, to be spread over long distances. Construction of the telescope is set to start in 2018, with early science observations in 2020.