Aug 12 2019

Targeted drug-delivery systems are a promising candidate for the effective treatment of cancer by leaving the healthy surrounding tissues unaffected. However, they can work only when the drug hits its target.

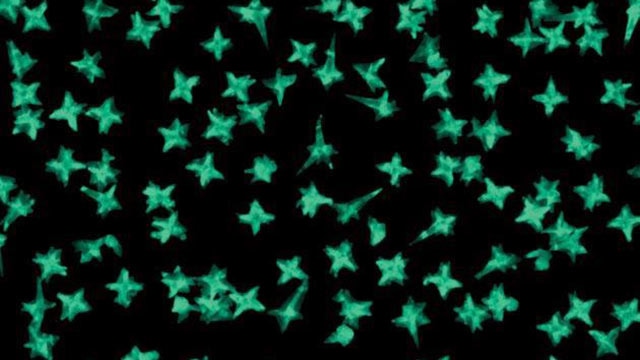

Gold nanostars have emerged as promising drug-delivery agents that can be designed to target cancer cells (Image credit: Northwestern University)

Gold nanostars have emerged as promising drug-delivery agents that can be designed to target cancer cells (Image credit: Northwestern University)

Scientists from Northwestern University have developed a new method to find whether single drug-delivery nanoparticles can successfully hit their expected targets—by just examining the distinct movements of each nanoparticle in real time.

They investigated drug-loaded gold nanostars on cancer cell membranes and discovered that nanostars developed to target cancer biomarkers passed over wide areas and rotated much rapidly than their non-targeting counterparts. The targeting nanostars, though surrounded by non-specifically bonded proteins, can retain their clear signature movements, showing that their targeting potential remains unrestrained.

Moving forward, this information can be used to compare how different nanoparticle characteristics—such as particle size, shape and surface chemistry—can improve the design of nanoparticles as targeting, drug-delivery agents.

Teri Odom, Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor of Chemistry, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University

The work led by Odom has been reported in ACS Nano on August 9th, 2019.

For quite a long time, the medical field has been seeking alternatives to existing cancer treatments, like radiation and chemotherapy, which damage healthy tissues besides diseased cells. Despite the fact that these are effective methods for cancer treatment, they pose the risks of painful or even dangerous side effects.

When drugs are delivered directly into the affected area—rather than destroying the entire body with treatment—targeted delivery systems can result in reduced side effects than existing treatment methods.

The selective delivery of therapeutic agents to cancer tumors is a major goal in medicine to avoid side effects. Gold nanoparticles have emerged as promising drug-delivery vehicles that can be synthesized with designer characteristics for targeting cancer cells.

Teri Odom, Charles E. and Emma H. Morrison Professor of Chemistry, Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences, Northwestern University

However, many proteins tend to attach to nanoparticles as they enter the body. Scientists began to worry about the hindrance of the targeting abilities of the particles these proteins might cause. The new imaging platform by Odom and her group can now analyze the developed nanoparticles to find whether their targeting function is retained in the presence of the adhered proteins.

The study titled “Revolving single-nanoconstruct dynamics during targeting and nontargeting live-cell membrane interactions” was supported by the National Institutes of Health (award number R01GM115763). Odom is a member of the International Institute for Nanotechnology, Chemistry of Life Processes Institute and Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center of Northwestern University.