Apr 7 2009

A Colorado State University mechanical engineering professor is in the first year of a new study to determine whether nanotubes on titanium implants can deliver chemotherapy drugs and antibiotics directly to skeletal implants, limiting the spread of drugs throughout the body and reducing side effects on patients.

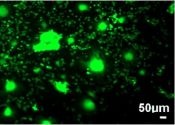

Cell growth on polymer wires made at CSU

Cell growth on polymer wires made at CSU

Ketul Popat, who teaches in the university's School of Biomedical Engineering, received a three-year $300,000 grant in 2008 from the National Science Foundation to study nanomedicine - scaling down the size of drug delivery vehicles so that the drugs can be delivered directly to the target organs with appropriate delivery rates. One of the first papers on the study appeared in the January issue of Nanotechnology magazine.

Colorado's Bioscience Discovery Evaluation Program, which aims to foster development of the bioscience industry in the state, also recently approved a grant of $57,000 for the research.

Popat and his four students are investigating whether tiny tubes of titanium adhered to the implant can be used to deliver drugs and increase bone growth on the implant surface. Titanium, which is an exceptionally hard and scratch-resistant material, has been used in prosthetic devices since the 1970s. Popat's team is taking the research to the next level: Will increasing the surface area of the titanium with a pattern of tiny tubes allow drugs to be delivered in a controlled way that will help regenerate the bone and keep the tissue healthy?

"We hope these nanotube arrays will mimic the complex geometries of natural tissue and will provide a porous mesh for the growth and maintenance of healthy cells," Popat said.

Popat said his team has hypothesized that applying nanotubes to the implant surface will result in increased cell growth. This cell growth on the implant surface will enhance the bond between the titanium implant and the bone, helping implants last longer. Typically implants must be replaced every eight to 10 years. However, by applying these nanotubes to the implant, they can be made more permanent inside the body, thus preventing further complicated surgeries in patients.

"Ultimately, if this kind of drug delivery system is found to be successful, it's going to improve the quality of life for people," Popat said. "Chemotherapy delivers up to 60 times more drugs than what is needed. We could release the drug for shorter or longer periods of time and keep the drug targeted to the tissue where is it needed so you won't realize you're taking a drug and there won't be any side effects."

Popat joined the Colorado State University College of Engineering in January 2008 as an assistant professor. He is working with Craig Grimes at Pennsylvania State University on the research.