Berkeley Lab researchers have produced non-toxic magnesium oxide nanocrystals that efficiently emit blue light and could also play a role in long-term storage of carbon dioxide, a potential means of tempering the effects of global warming.

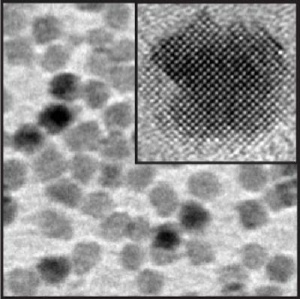

This is a high resolution electron micrograph image of magnesium oxide nanocrystals; the inset shows a single nanocrystal. Credit: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

This is a high resolution electron micrograph image of magnesium oxide nanocrystals; the inset shows a single nanocrystal. Credit: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory

In its bulk form, magnesium oxide is a cheap, white mineral used in applications ranging from insulating cables and crucibles to preventing sweaty-palmed rock climbers from losing their grip. Using an organometallic chemical synthesis route, scientists at the Molecular Foundry have created nanocrystals of magnesium oxide whose size can be adjusted within just a few nanometers. And unlike their bulk counterpart, the nanocrystals glow blue when exposed to ultraviolet light.

Current routes for generating these alkaline earth metal oxide nanocrystals require processing at high temperatures, which causes uncontrolled growth or fusing of particles to one another-not a desirable outcome when the properties you seek are size-dependent. On the other hand, vapor phase techniques, which provide size precision, are time and cost intensive, and leave the nanocrystals attached to a substrate.

"We've discovered a fundamentally new, unconventional mechanism for nicely controlling the size of these nanocrystals, and realized we had an intriguing and surprising candidate for optical applications," said Delia Milliron, Facility Director of the Inorganic Nanostructures Facility at Berkeley Lab's nanoscience research center, the Molecular Foundry. "This efficient, bright blue luminescence could be an inexpensive, attractive alternative in applications such as bio-imaging or solid-state lighting."

Unlike conventional incandescent or fluorescent bulbs, solid-state lighting makes use of light-emitting semiconductor materials-in general, red, green and blue emitting materials are combined to create white light. However, efficient blue light emitters are difficult to produce, suggesting these magnesium oxide nanocrystals could be a bright candidate for lighting that consumes less energy and has a longer lifespan.

These minute materials do more than glow, however. Along with their promising optical behavior, these magnesium oxide nanocrystals will be a subject of study in an entirely different field of research: Berkeley Labs' Energy Frontier Research Center (EFRC) for Nanoscale Control of Geologic CO2, designed to "establish the scientific foundations for the geological storage of carbon dioxide."

Experts say carbon dioxide capture and storage will be vital to achieving significant cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, but the success of this technology hinges on sealing geochemical reservoirs deep below the earth's surface without allowing gases or fluids to escape. If properly stored, the captured carbon dioxide pumped underground forms carbonate minerals with the surrounding rock by reacting with nanoparticles of magnesium oxide and other mineral oxides.

"These nanocrystals will serve as a test system for modeling the kinetics of dissolution and mineralization in a simulated fluid-rock reservoir, allowing us to probe a key pathway in carbon dioxide sequestration," said Jeff Urban, a staff scientist in the Inorganic Nanostructures Facility at the Molecular Foundry who is also a member of the EFRC research team. "The geological minerals that fix magnesium into a stable carbonate are compositionally complex, but our nanocrystals will provide a simple model to mimic this intricate process."

Hoi Ri Moon, a post-doctoral researcher at the Foundry working with Milliron and Urban, noted her team's direct synthesis method could also be helpful for already-established purposes. "As a user facility that provides support to nanoscience researchers around the world, we would like to pursue studies with other scientists who could use our nanocrystals as 'feedstock' for catalysis, another application for which magnesium oxide thin films are commonly used," said Moon.

More information: "Size-controlled synthesis and optical properties of monodisperse colloidal magnesium oxide nanocrystals," by Hoi Ri Moon, Jeffrey J. Urban and Delia J. Milliron, appears in Angewandte Chemie International Edition .