Aug 27 2009

Small interfering RNA (siRNA), a type of genetic material, can block potentially harmful activity in cells, such as tumor cell growth. But delivering siRNA successfully to specific cells without adversely affecting other cells has been challenging.

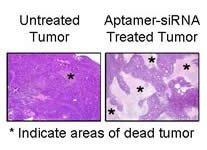

A mouse tumor treated with an aptamer-siRNA combination (right) shows many dead areas (indicated by the asterisks), whereas an untreated tumor (left) is still largely intact. Delivering siRNA successfully to specific cells has been challenging. UI researchers modified siRNA so that it could be injected into the bloodstream and impact only targeted cells.

A mouse tumor treated with an aptamer-siRNA combination (right) shows many dead areas (indicated by the asterisks), whereas an untreated tumor (left) is still largely intact. Delivering siRNA successfully to specific cells has been challenging. UI researchers modified siRNA so that it could be injected into the bloodstream and impact only targeted cells.

University of Iowa researchers have modified siRNA so that it can be injected into the bloodstream and impact targeted cells while producing fewer side effects. The findings, which were based on animal models of prostate cancer, also could make it easier to create large amounts of targeted therapeutic siRNAs for treating cancer and other diseases. The study results appeared online Aug. 23 in the journal Nature Biotechnology.

"Our goal was to make siRNA deliverable through the bloodstream and make it more specific to the genes that are over expressed in cancer," said the study's senior author Paloma Giangrande, Ph.D., assistant professor of internal medicine and a member of Holden Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In previous research completed at Duke University, Giangrande's team showed that a compound called an aptamer can be combined with siRNA to target certain genes. When the combined molecule is directly injected into tumors in animal models, it triggers the processes that stop tumor growth. However, directly injecting the combination into tumors in humans is difficult.

In the new study, the researchers trimmed the size of a prostate cancer-specific aptamer and modified the siRNA to increase its activity. Upon injection into the bloodstream, the combination triggered tumor regression without affecting normal tissues.

Making the aptamer-siRNA combination smaller makes it easier to produce large amounts of it synthetically, Giangrande said.

The team also addressed the problem that large amounts of siRNA are needed since most of it gets excreted by the kidneys before having an effect. To keep siRNA in the body longer and thereby use less of it, the team modified it using a process called PEGlyation.

"If you want to use siRNA effectively for clinical use, especially for cancer treatment, you need to deliver it through an injection into the bloodstream, reduce the amount of side effects and be able to improve its cost-effectiveness. Our findings may help make these things possible," Giangrande said.

Although the current study focused on prostate cancer, the findings could apply to other cancers and diseases. Giangrande said the next step is to test the optimized aptamer-siRNA compound in a larger animal model.

Other researchers who contributed significantly to the study included James McNamara, Ph.D., and Anton McCaffrey, Ph.D., both UI assistant professors of internal medicine.

The study was supported by an American Cancer Society Institutional Research grant and a Lymphoma SPORE Development Research Award.