Dec 18 2009

Nanotechnology has already made it to the shelves of your local pharmacy and grocery: nanoparticles are found in anti-odor socks, makeup, makeup remover, sunscreen, anti-graffiti paint, home pregnancy tests, plastic beer bottles, anti-bacterial doorknobs, plastic bags for storing vegetables, and more than 800 other products.

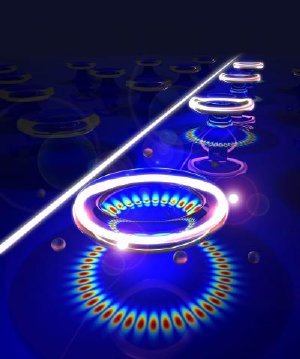

The high-Q microresonators could be mass produced by the hundreds of thousands on silicon wafers. Each torus is 20 to 30 micrometers across, one-tenth the size of the period at the end of this sentence. In this image, two particles (bright spots) have landed on the closest microresonator and are acting as scattering centers that disturb the light waves in the torus. This allows them to be detected and measured. Credit: Image by Jiangang Zhu and Jingyang Gan/WUSTL

The high-Q microresonators could be mass produced by the hundreds of thousands on silicon wafers. Each torus is 20 to 30 micrometers across, one-tenth the size of the period at the end of this sentence. In this image, two particles (bright spots) have landed on the closest microresonator and are acting as scattering centers that disturb the light waves in the torus. This allows them to be detected and measured. Credit: Image by Jiangang Zhu and Jingyang Gan/WUSTL

How safe are these products and the flood of new ones about to spill out of labs across the world? A group of researchers at Washington University is devising instruments and protocols to assess the impact of nanoparticles on the environment and human health before they are sent to market

As part of this effort, a team led by Lan Yang, Ph.D., assistant professor of electrical and systems engineering, has devised a sensor on a chip that can not only detect but also measure single particles. They expect the sensor will be able to measure nanoparticles smaller than 100 nanometers in diameter (about the size of a virus particle) on the fly.

The new sensor, an improved version of a sensor called a whispering-gallery microresonator, is described in the December 13 edition of Nature Photonics's advanced online publication.

Whispering-gallery microresonators

In a miniature version of a whispering gallery, laser light is coupled into a circular "waveguide," such as a glass ring. When the light strikes the boundary of the ring at a grazing angle it is reflected back into the ring.

The light wave can make many trips around the ring before it is absorbed, but only frequencies of light that fit perfectly into the circumference of the ring can do so. If the circumference is a whole number of wavelengths, the light waves superimpose perfectly each trip around.

This perfect match between the frequency and the circumference is called a resonance, or whispering-gallery mode.

The glass resonator can serve as a particle detector because the faint outer edge of the light wave, called its "evanescent tail, " penetrates the ring's surface, probing the surroundings. So when a particle attaches to the ring, it disturbs the light wave, changing the resonant frequency. This change can be used to measure the size of the particle.

There are two problems with these microresonators, says Yang. One is that they are finicky. Lots of things can shift the resonant frequency, including vibration or temperature changes.

The other is that the frequency shift depends on where the particle lands on the ring. A particle that happens to land on a node (the dark blue areas reflected on the base of the pedestal in the accompanying image) will disturb the light wave less and appear smaller than a particle of the same size that happens to land on an anti-node (the red spots visible on the base).

For this reason the frequency shift is not a reliable measure of particle size.

The ultra-high-Q microresonator

The way around these problems is a self-referring sensing scheme possible only in an exceptionally good resonator, one with virtually no optical flaws.

Yang's lab uses surface tension to achieve the necessary perfection. The microresonators are etched out of glass layers on silicon wafers by techniques borrowed from the integrated circuit industry. These techniques allow the rings to be mass produced but leave them with rough surfaces.

In a crucial finishing step, the microresonators are reheated with a pulsed laser until the glass reflows. Surface tension then pulls the rings into smooth toruses.

"Nature helps us create the perfect structure," says Yang.

"This quality factor gives the sensor a resonance as beautiful as the pure tone form the finest musical instrument," says Jiangang Zhu, a graduate student in Yang's lab.

The Q value, or quality factor, of the reflowed resonators, a measure of microscopic imperfections that sap energy from the resonating mode, is about 100 million, meaning that light circles the ring many time. Because recirculation dramatically increases the interaction of the light wave and particles on the ring's surface, a different approach to particle detection is possible: mode splitting.

Each whispering-gallery mode is actually two modes: the light travels both clockwise and counterclockwise around the resonator. These modes are usually "degenerate," meaning they have the same frequency.

When a particle lands on a resonator, it acts as a scattering center that couples energy between the modes. The two modes re-arrange themselves so that the particle lies on a node of one and an anti-node of the other. As a result, one wave is much more perturbed than the other, and this "lifts the degeneracy," or "splits the mode."

In a low-Q resonator, the split mode can't be resolved. But in the high-Q resonator it is easily seen.

A sensor that relies on mode splitting is much less finicky than a frequency-shifting sensor. Because the clockwise and counterclockwise light waves share the same resonator, they share the same noise. Any jitter or jiggle that biases one biases the other by the same amount. Because it is self-referring, the sensor is more accurate and reliable.

Mode splitting also solves the particle location problem. The light scattering that perturbs the mode also broadens it. The mode split still varies with the location of the particle, but the ratio of the mode split and the difference between the linewidths (the breadth) of the two modes depends only on the particle's size.

To test the sensor, Daren Chen, Ph.D., associate professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering, helped the team generate nanoparticles within specifc size ranges. In experiments with nanoparticles of salt or nanospheres of plastic, the resonator's size estimates were within one or two percent of the actual values.

"Size is a key parameter that significantly affects the physical and chemical properties of nanoparticles," says Yang. "It plays a crucial role in the applications of nanoparticles both in science and in industry, all of which will benefit from the ability to measure these particles accurately."