May 11 2010

ETH-Zurich researchers have developed a new kind of sensor that can immediately gauge whether a person is suffering from type 1 diabetes upon coming into contact with their breath.

Acetone is also found in a healthy person’s breath, but the concentration is only about 900 ppb (particles per billion); in people suffering from type 1 diabetes, however, the concentration is double that; and in the case of a ketoacidosis it can be even higher. That’s why the sensor developed at ETH Zurich works so well: it can detect as few as 20 ppb of acetone and even works at extremely high humidity levels of over 90 percent – like in the human breath.

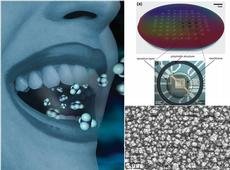

Exhaled air from diabetics contains slightly higher levels of acetone vapor than healthy persons. A new kind of sensor (a) can now selectively detect acetone even in the smallest concentrations; this is due to a layer of a unique crystal phase of tungsten oxide, which thanks to a special procedure becomes porous like a sponge. (Photos: ETH Zurich)

Exhaled air from diabetics contains slightly higher levels of acetone vapor than healthy persons. A new kind of sensor (a) can now selectively detect acetone even in the smallest concentrations; this is due to a layer of a unique crystal phase of tungsten oxide, which thanks to a special procedure becomes porous like a sponge. (Photos: ETH Zurich)

Flame-made Nanosensors

Sotiris Pratsinis, professor of particle technology at the Institute of Process Engineering, and his team showcased the novel sensor on May 1 in the journal Analytical Chemistry of the American Chemical Society. They used a substrate with gold electrodes for the sensor and coated it with an ultra-thin semiconductor film made of nanoparticles. These particles consisted of tungsten oxide mixed with silicon, thus greatly improving the sensitivity of the sensor. The mixture is produced in a flame at a temperature of over 2200° C; the nanoparticles rise in a greenish-yellow cloud and are collected on the carrier substrate, which the researchers then cool with water. Through this rapid heating and cooling, a vitreous semiconductor layer forms on the electrodes stably capturing.the metastable crystalline phase of epsilon tungsten oxide that resonates with acetone giving its required high selectivity for undisputable detection of acetone vapor in the human breath.

Using high-resolution electron microscopes, the researchers observed that the deposited material exhibited an unusual spongy structure. The acetone molecules get caught up in the pores and begin to react with the tungsten oxide; if the breath contains relatively high acetone concentrations (> 1800 ppm), the electrical resistance of the material drops drastically and thus more electricity flows between the electrodes generating a correspondingly strong signal. For lower concentrations of acetone, on the other hand, the resistance drops significantly less.

Implications

In the future, ETH-Zurich professor Sotiris Pratsinis also hopes to develop materials that would be able to detect other chronic illnesses by breath analysis using such sensors. As far as diabetes sufferers are concerned, a handy, easy-to-use device would make a huge difference; it would mean they could make their own quick and easy diagnoses instead of taking blood samples to measure the blood sugar level, as they have had to do up to now, making the irksome daily finger-pricks a thing of the past. Sensors like this could also be put to good use in hospital emergency rooms, where it would provide a fuss-free method of establishing whether a patient has suffered a diabetic ketoacidosis.

Wanted: partner from medicine

The sensor is just a prototype for now; however, Pratsinis is currently on the lookout for a partner from medicine to turn it into a measuring device for everyday use.

Non-invasive methods to diagnose illnesses are becoming increasingly important and being fast, cheap and easy to use breath analysis is a key aspect in lowering the spiraling medical costs. The breath mainly consists of a mixture of nitrogen, oxygen, carbon dioxide and water, along with over 1,000 volatile substances that are only present in very small concentrations; these also include volatile organic compounds produced by the body itself. Some are typical for particular illnesses and serve as markers – like acetone for type-1 diabetes.

The project was made possible by highly motivated associates, Marco Righettoni, PhD student, and Dr. Antonio Tricoli of the Particle Technology Laboratory at the Department of Mechanical and Process Engineering that were funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation, European Space Agency and CCMX-NANCER. Antonio Tricoli was nominated for the Material Research Prize 2010, which will be awarded at the MRC Graduate Symposium on May 10.