Jeffrey Long's lab will soon host a round-the-clock, robotically choreographed hunt for carbon-hungry materials. The Berkeley Lab chemist leads a diverse team of scientists whose goal is to quickly discover materials that can efficiently strip carbon dioxide from a power plant's exhaust, before it leaves the smokestack and contributes to climate change.

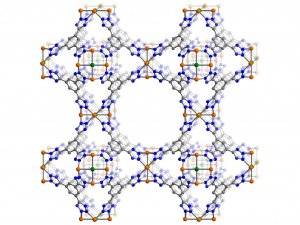

More than a football field of surface area in the palm of your hand. Can scientists fashion metal-organic frameworks, seen in this illustration, into carbon-absorbing sponges? Will the material work in a power plant? Berkeley Lab scientists hope to find out soon.

More than a football field of surface area in the palm of your hand. Can scientists fashion metal-organic frameworks, seen in this illustration, into carbon-absorbing sponges? Will the material work in a power plant? Berkeley Lab scientists hope to find out soon.

They're betting on a recently discovered class of materials called metal-organic frameworks that boast a record-shattering internal surface area. A sugar cube-sized piece, if unfolded and flattened, would more than blanket a football field. The crystalline material can also be tweaked to absorb specific molecules.

The idea is to engineer this incredibly porous compound into a voracious sponge that gobbles up carbon dioxide.

And they're going for speed. The scientists hope to discover this dream material in a breakneck three years, maybe sooner. To do this, they'll create an automated system that simultaneously synthesizes hundreds of metal-organic frameworks, then screens the most promising candidates for further refinement.

"Our discovery process will be up to 100 times faster than current techniques," says Long. "We need to quickly find next-generation materials that capture and release carbon without requiring a lot of energy."

Carbon capture is the first step in carbon capture and storage, a climate change mitigation strategy that involves pumping compressed carbon dioxide captured from large stationary sources into underground rock formations that can store it for geological time scales. Many scientists, including the United Nations' Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, believe that the technology is key to curbing the amount of carbon dioxide that enters the atmosphere. Fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas will likely remain cheap and plentiful energy sources for decades to come — even with the continued development of renewable energy sources.

Carbon capture and storage is being tested on a large scale in only a few places worldwide. One of the biggest obstacles to industrial-scale implementation is its parasitic energy cost. Today's carbon capture materials, such as liquid amine scrubbers, sap a whopping 30 percent of the power generated by a power plant.

To overcome this, scientists are seeking alternatives that can be used again and again with minimal energy costs. It's a slow, finicky process. Promising materials such as metal-organic frameworks come in millions of variations, only a handful of which are conducive to capturing carbon. Finding just the right material may take years.

That could change. In early May, Long's team began negotiating a three-year, $3.6 million grant from the Department of Energy's Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy (ARPA-E) to supercharge the search.

"We want to run the discovery process very rapidly and find materials that only consume 10 percent of a power plant's energy," says Long, who's working with fellow Berkeley Lab scientists Maciej Haranczyk, Eric Masanet, Jeffrey Reimer, and Berend Smit on the project. Together, they'll create a state-of-the-art production line.

A robot will automatically synthesize hundreds of metal-organic frameworks and X-ray diffraction will offer a first-pass evaluation in the search for pure new materials. Magnetic resonance spectroscopy will then ferret out the materials with the pore size distribution best suited for carbon capture.

Next comes the big test: can it capture carbon dioxide from a flue gas? High-throughout gas sorption analysis conducted using new instrumentation built by Wildcat Discovery Technologies of San Diego, California will provide the answer.

Computer algorithms will constantly churn through the resulting data and help refine the next round of synthesis. Promising materials will also be assessed to determine if any ingredients are too expensive for large-scale commercialization.

"We don't want to discover a great material and find it's so expensive that no one will use it," says Long.

As a final test, the Electric Power Research Institute will predict the utility of the best new materials in an industrial-scale carbon capture process.

"We need to find the optimum range of metal-organic frameworks for each power plant," says Long. "Ultimately, this research is intended to lead to materials worthy of large-scale testing and commercialization."