Oct 20 2010

Plants play an important role as producers of sugar and carbohydrates. Scientists from the University of Würzburg are conducting research in this area – with the long-term goal of influencing sugar levels in agricultural crop plants.

The sugar that is consumed by people is obtained predominantly from sugar cane and sugar beets. Plants produce the sweet, energy-rich substance during photosynthesis in their leaves. From there they transport it in the form of sucrose through the phloem network to those tissues that do not perform photosynthesis and which are therefore reliant on sugar imports, such as roots and fruits.

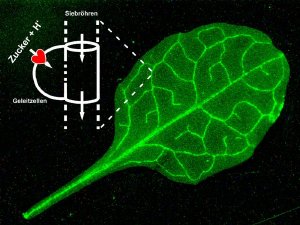

Leaf of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, in which the sucrose transporters are visible. They have been labeled with a fluorescent protein. The transporters are located along the phloem network, the so-called sieve tubes, through which sugar-containing juice flows.

Image: Dietmar Geiger

Leaf of the plant Arabidopsis thaliana, in which the sucrose transporters are visible. They have been labeled with a fluorescent protein. The transporters are located along the phloem network, the so-called sieve tubes, through which sugar-containing juice flows.

Image: Dietmar Geiger

A key contributor to sugar distribution in the plant is a central molecule known as the sucrose transporter. This is located in the phloem cell membranes and delivers a truly outstanding performance. Dietmar Geiger from the University of Würzburg has measured this and is now describing the transporter as a “quite seamlessly operating nanomachine”.

Strong transport performance in the face of high resistance

A single transporter pumps up to 500 sucrose molecules a second through the cell membrane into the phloem network. To do this it overcomes great resistance: even if the network is already packed with sugar, it is still able to force more in – until a concentration is reached that borders on the solubility limit for sucrose. This performance is comparable to the effort involved in pumping up a tire: the more air the tire contains, the harder it is to pump.

The high accumulation of sugar in the phloem network increases the pressure there. At the same time, however, pressure is also released from the vascular system: in the tissues that are supplied with sugar. Consequently, the difference in pressure makes the sugar-containing juice flow in the plant to wherever sugar is consumed. “In the same way as the heart is responsible for circulating blood in people, the sucrose transporters in plants make sure that the sugar juice flows,” says Geiger.

Findings published in the magazine PLoS one

The function of sucrose transporters in maize plants is described in detail by the Würzburg plant physiologist and biophysicist Geiger in the journal PLoS one. His Würzburg colleagues Rainer Hedrich and Hermann Koepsell were also involved with the publication, as were scientists from Frankfurt am Main and Genoa.

The results were achieved with the help of eggs from the South African clawed frog, which the researchers are using as living test tubes. They introduce the gene for the sucrose transporter into the eggs, where active transporters are produced from it and integrated into the membrane. “This makes the transport protein accessible for biophysical measurements,” explains Geiger. Using this technique, the scientists have managed, among other things, to demonstrate for the first time that a transport protein can be responsible for both loading and unloading the phloem network under physiological conditions.

Further research into the inner molecular workings of the transporter

The German Research Foundation (DFG) is funding Dietmar Geiger’s work so that he can continue to extend knowledge of the inner molecular workings of these sugar-transporting machines. Geiger is currently focusing on the structural and functional requirements that allow the transporter to carry sucrose molecules through membranes accurately and with maximum efficiency.

Geiger and his colleagues are aiming to dismantle the transporter’s mechanism into its constituent parts using new biophysical methods. One of their plans is to attach a fluorescent molecule to a transporter site that moves during the transport operation. By observing the fluorescence they will then be able to look on “live” while the transporter is at work.

Long-term goal: to optimize agricultural crop plants

“The long-term goal of our work is to optimize the distribution and storage of important sugar compounds in plants used agriculturally,” says Dietmar Geiger. He adds that fungal attacks on useful plants, for example, lead to considerable crop failures year after year. Fungi also possess sucrose transporters that they use to absorb sugar – and these work even more efficiently than those of plants. As a result, they undermine the supply of energy-rich sugar compounds to the plant. “Equipping plants with similarly efficient sucrose transporters could decide the battle for sugar resources in favor of the plant and reduce crop failures,” explains Geiger.

Having researched the principle behind the function of sucrose transporters, the scientists will examine whether the precise adjustment of the sugar content in the plant’s phloem network depends solely on import and export. Or is the sugar level in plants regulated by sensors, as with the insulin system in people? Intervention in such a sugar sensor system would make it possible to control and increase the biomass production of plants used agriculturally.

“Sucrose- and H+-Dependent Charge Movements Associated with the Gating of Sucrose Transporter ZmSUT1”, Armando Carpaneto, Hermann Koepsell, Ernst Bamberg, Rainer Hedrich, Dietmar Geiger, PloS one, September 2010, Vol. 5, Issue 9: e12605. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012605