Oct 18 2012

There's a new contender in the race to find an inexpensive alternative to platinum catalysts for use in hydrogen fuel cells.

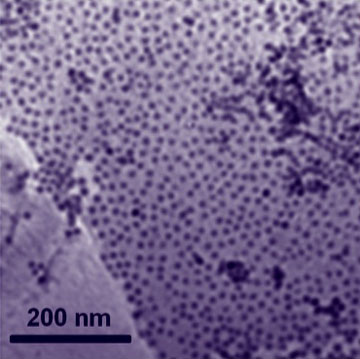

Nanoparticles of cobalt attach themselves to a graphene substrate in a single layer. As a catalyst, the cobalt-graphene combination was a little slower getting the oxygen reduction reaction going, but it reduced oxygen faster and lasted longer than platinum-based catalysts. (credit: Sun Lab/Brown University)

Nanoparticles of cobalt attach themselves to a graphene substrate in a single layer. As a catalyst, the cobalt-graphene combination was a little slower getting the oxygen reduction reaction going, but it reduced oxygen faster and lasted longer than platinum-based catalysts. (credit: Sun Lab/Brown University)

Brown University chemist Shouheng Sun and his students have developed a new material — a graphene sheet covered by cobalt and cobalt-oxide nanoparticles — that can catalyze the oxygen reduction reaction nearly as well as platinum does and is substantially more durable.

The new material "has the best reduction performance of any nonplatinum catalyst," said Shaojun Guo, postdoctoral researcher in Sun's lab and lead author of a paper published online in the journal Angewandte Chemie International Edition.

The oxygen reduction reaction occurs on the cathode side of a hydrogen fuel cell. Oxygen functions as an electron sink, stripping electrons from hydrogen fuel at the anode and creating the electrical pull that keeps the current running through electrical devices powered by the cell. "The reaction requires a catalyst, and platinum is currently the best one," said Sun. "But it's very expensive and has a very limited supply, and that's why you don't see a lot of fuel cell use aside from a few special purposes."

Thus far scientists have been unable to develop a viable alternative. A few researchers, including Sun and Guo, have developed new catalysts that reduce the amount of platinum required, but an effective catalyst that uses no platinum at all remains elusive.

This new graphene-cobalt material is the most promising candidate yet, the researchers say. It is the first catalyst not made from a precious metal that comes close to matching platinum's properties.

Lab tests performed by Sun and his team showed that the new graphene-cobalt material was a bit slower than platinum in getting the oxygen reduction reaction started, but once the reaction was going, the new material actually reduced oxygen at a faster pace than platinum. The new catalyst also proved to be more stable, degrading much more slowly than platinum over time. After about 17 hours of testing, the graphene-cobalt catalyst was performing at around 70 percent of its initial capacity. The platinum catalyst the team tested performed at less than 60 percent after the same amount of time.

Cobalt is an abundant metal, readily available at a fraction of what platinum costs. Graphene is a one-atom-thick sheet of carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb structure. Developed in the last few years, graphene is renowned for its strength, electrical properties, and catalytic potential.

Self-assembly process

Often, graphene nanoparticle materials are made by growing nanoparticles directly on the graphene surface. But that process is problematic for making a catalyst, Sun said. "It's really difficult to control the size, shape, and composition of nanoparticles," he said.

Sun and his team used a self-assembly method that gave them more control over the material's properties. First, they dispersed cobalt nanoparticles and graphene in separate solutions. The two solutions were then combined and pounded with sound waves to make sure they mixed thoroughly. That caused the nanoparticles to attach evenly to the graphene in a single layer, which maximizes the potential of each particle to be involved in the reaction. The material was then pulled out of solution using a centrifuge and dried. When exposed to air, outside layers of atomic cobalt on each nanoparticle are oxidized, forming a shell of cobalt-oxide that helps protect the cobalt core.

The researchers could control the thickness of the cobalt-oxide shell by heating the material at 70 degrees Celsius for varying amounts of time. Heating it longer increased the thickness of the shell. This way, they could fine-tune the structure in search of a combination that gives top performance. In this case, they found that a 1-nanometer shell of cobalt-oxide optimized catalytic properties.

Sun and his team are optimistic that with more study their material could one day be a suitable replacement for platinum catalysts. "Right now, it's comparable to platinum in an alkaline medium," Sun said, "but it's not ready for use yet. We still need to do more tests."

Ultimately, Sun says, finding a suitable nonplatinum catalyst is the key to getting fuel cells out of the laboratory phase and into production as power sources for cars and other devices.