Nov 9 2012

A study published by Andrea Vanossi, Nicola Manini and Erio Tosatti - three SISSA researchers - in PNAS (Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) provides a new tool to better understand how sliding friction works in nanotribology, through colloidal crystals.

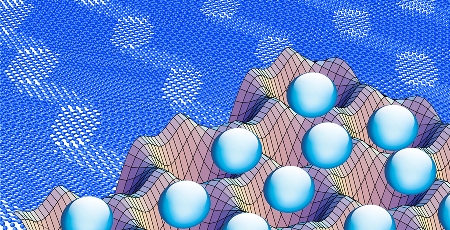

Credit: SISSA

Credit: SISSA

By theoretically studying these systems of charged microparticles, researchers are able to analyze friction forces through molecular dynamics simulations with accuracy never experienced before.

"There are several and very concrete potentialities", stated Andrea Vanossi, one of the members of the research group. "Just think of the constant miniaturization of high-tech components and of all the different nanotechnology sectors: if we understand how friction works at these levels, we will be able to create even more effective molecular motors or functional microsystems".

Colloidals are part of our everyday life (e.g. milk, asphalt or smoke) and they differentiate according to the state of the dispersed and dispersing substance (liquid, solid or gaseous).

The simulations were performed by SISSA in collaboration with ICTP, the Department of Physics in Milan and the CNR-IOM Institute for Materials Manufacturing and they allowed understanding what happens when a colloidal monolayer slides against an optical reticle modifying some parameters such as surface corrugation, drift speed or contact geometry.

The research method is also something new. Before this simulation was performed, only some recent experiments carried out in Germany tried for the first time to describe the behaviour of individual particles of a colloid in friction conditions, but never in such a precise way.

More in detail, researchers also suggest a way to directly extract the energy lost in friction by using the sliding data of the colloid. "This study is innovative also because it will allow predicting the different regimes of static friction realized according to the density of colloids and the strength of the optical reticle", added Erio Tosatti, another member of the research group. "All this lets us assume that crystalline solid surfaces will act in a similar way. We have never been able to make such a hypothesis before".

This study will open the way to new systems to explore the complexity of similar events, maybe at a microscopic scale.