Duke University engineers are layering atom-thick lattices of carbon with polymers to create unique materials with a broad range of applications, including artificial muscles.

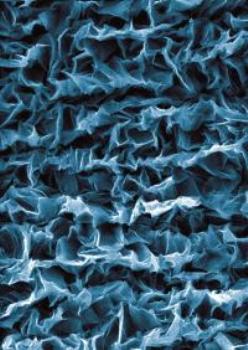

This is crumpled graphene. Credit: Xuanhe Zhao

This is crumpled graphene. Credit: Xuanhe Zhao

The lattice, known as graphene, is made of pure carbon and appears under magnification like chicken wire. Because of its unique optical, electrical and mechanical properties, graphene is used in electronics, energy storage, composite materials and biomedicine.

However, graphene is extremely difficult to handle in that it easily "crumples." Unfortunately, scientists have been unable to control the crumpling and unfolding of large-area graphene to take advantage of its properties.

Duke engineer Xuanhe Zhao, assistant professor in Duke's Pratt School of Engineering, likens the challenge of controlling graphene to the difference between unfolding paper and wet tissue.

"If you crumpled up normal paper, you can pretty easily flatten it out," Zhao said. "However, graphene is more like wet tissue paper. It is extremely thin and sticky and difficult to unfold once crumpled. We have developed a method to solve this problem and control the crumpling and unfolding of large-area graphene films."

The Duke engineers attached the graphene to a rubber film that had been pre-stretched to many times its original size. Once the rubber film was relaxed, parts of the graphene detached from the rubber while other parts kept adhering to it, forming an attached-detached pattern with a feature size of a few nanometers. As the rubber relaxed, the detached graphene was compressed to crumple. But as the rubber film was stretched back, the adhered spots of graphene pulled on the crumpled areas to unfold the sheet.

"In this way, the crumpling and unfolding of large-area, atomic-thick graphene can be controlled by simply stretching and relaxing a rubber film, even by hands," Zhao said.

The results were published online in the journal Nature Materials.

"Our approach has opened avenues to exploit unprecedented properties and functions of graphene," said Jianfeng Zang, a postdoctoral fellow in Zhao's group and the first author of the paper. "For example, we can tune the graphene from being transparent to opaque by crumpling it, and tune it back by unfolding it."

In addition, the Duke engineers layered the graphene with different polymer films to make a "soft" material that can act like muscle tissues by contracting and expanding on demand. When electricity is applied to the graphene, the artificial muscle expands in area; when the electricity is cut off, it relaxes. Varying the voltage controls the degree of contraction and relaxation.

"The crumpling and unfolding of graphene allows large deformation of the artificial muscle," Zang said.

"New artificial muscles are enabling diverse technologies ranging from robotics and drug delivery to energy harvesting and storage," Zhao said. "In particular, they promise to greatly improve the quality of life for millions of disabled people by providing affordable devices such as lightweight prostheses and full-page Braille displays."