Mar 1 2013

With crisp resolution to 100 nanometers -- a typical germ is about 1,000 nanometers -- the DeltaVision OMX imaging system is considered one of the world's finest microscope systems. Upon its arrival to Indiana University Bloomington's Light Microscopy Imaging Center in 2010, researchers quickly renamed it the "OMG" microscope for the amazing images it produced and for its ability to do super-speed imaging of multiple-labeled proteins in cells.

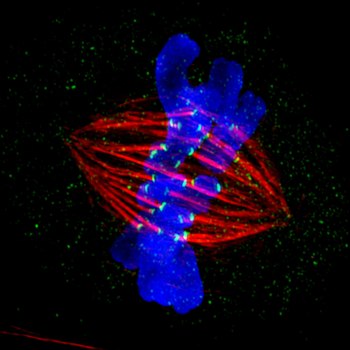

A metaphase epithelial cell stained for microtubules (red), kinetochores (green) and DNA (blue), was the winning image, submitted by IU, in the 2012 GE Healthcare Life Sciences Cell Imaging Competition. The DNA here is fixed in the process of being moved along the microtubules that form the structure of the spindle. Courtesy: Indiana University

A metaphase epithelial cell stained for microtubules (red), kinetochores (green) and DNA (blue), was the winning image, submitted by IU, in the 2012 GE Healthcare Life Sciences Cell Imaging Competition. The DNA here is fixed in the process of being moved along the microtubules that form the structure of the spindle. Courtesy: Indiana University

Today one of those images -- a stunning image taken by longtime IU research associate Jane Stout of a dividing mammalian cell with chromosomes shown aligned on cell division machinery at the sites of attachment -- was announced as a winner in the international GE Healthcare Life Sciences 2012 Cell Imaging Competition.

Stout conducts research in the laboratory of Claire Walczak, a professor of biochemistry and molecular biology in IU Bloomington's Medical Sciences Program, a branch of the IU School of Medicine. Walczak is also executive director of the Light Microscopy Imaging Center in Myers Hall, where the $1.2 million OMX microscope system resides. IU purchased the super-resolution microscope with funds provided solely through the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009.

"Some of us affectionately renamed it 'OMG' after we saw the images it could produce," Stout recalled. "This instrument, one of only a handful in the world, allows us to see details inside the cells at previously unprecedented resolution."

Stout acknowledged that the initial investment for the microscope was high, but the methodology to use the scope is relatively fast, cheap and highly reproducible, all of which allows researchers to process and image many cells and to look at many different players in this process. The microscope even allows scientists to watch mitosis -- the process of chromosome separation into two identical sets -- in living cells using fluorescently tagged proteins.

Walczak's lab, whose work is funded by the National Institutes of Health, is interested in a specific family of proteins involved in attaching and moving DNA along a subcellular structure called a spindle that separates chromosomes during cell division. The protein family also helps to rearrange the spindle structure itself, and both of these processes occur countless times within humans throughout life, all with an astonishingly high degree of accuracy and precision.

"This particular high-resolution image allowed us to see individual strands within bundles of specialized structures that form the spindle, whereas before we could only infer the bundled structure from other types of imaging and assays," Stout said. "In future images, we hope to see where the different members of the protein family act on the spindle to learn how their movements are coordinated to regulate the entire process of DNA segregation."

By understanding how duplicated DNA is segregated properly, the researchers hope to gain the knowledge of how to repair the process when things go wrong, as it does in cancer, Walczak noted.

"From the time of conception, the fertilized egg must go through hundreds of thousands of divisions that contribute to the assembly of the different parts of our bodies," she said. "After birth, many cell types continue to divide as the organism grows or to replenish cells that have died off. However, cell division may not always be perfect, and cell division gone awry is a hallmark of cancer. To understand both the good and the bad of a biological process, such as cell division, scientists often try to see what is going on inside the cell."

Using a very powerful microscope like the OMX that uses a combination of optics and computer-aided reconstructions to break the diffraction barrier of light, along with special reagents used to label individual cell parts, scientists can see whether things are put together correctly or not.

For her prize-winning image, and the sole winner in the high-resolution and super-resolution microscopy division of the competition, Stout and a guest will travel to New York City in April and see the image displayed on an electronic billboard in Times Square.

"This contest and others like it create the chance to show the public what we do and publicize the need for our work to be valued," she said. "We in the scientific community are passionate about the world we live in and amazed at how interconnected it all is. Most of us will never get rich doing what we do, and we often work insane hours, sometimes merely to see beauty through the eyepiece of a microscope. We are driven to understand the world around us to better how everyone lives in it, and we rely on people's appreciation of what we do, and the public funding, to allow us to continue that goal."

The GE Healthcare Life Sciences 2012 Cell Imaging Competition celebrates the exceptional research of scientists across the world using IN Cell Analyzer, DeltaVision Elite and DeltaVision OMX systems in their work. The OMX is built by Applied Precision, a GE Healthcare company; and public, online voting for the competition ran from Nov. 19 through Jan. 2. Attendees of last year's annual meetings of the American Society for Cell Biology and the Molecular Biology Society of Japan were also invited to vote for their favorite. In all, over 100 images were received in the competition and more than 15,000 votes were cast.

Additional winning images and a full gallery of the 2012 Cell Imaging Competition are also available.