What would you do with a camera that can take a picture of something and tell you how new it is? If you’re Berkeley Lab scientists Katherine Louie, Ben Bowen, Jian-Hua Mao and Trent Northen, you use it to gain a better understanding of the ever-changing world of metabolites, the molecules that drive life-sustaining chemical transformations within cells.

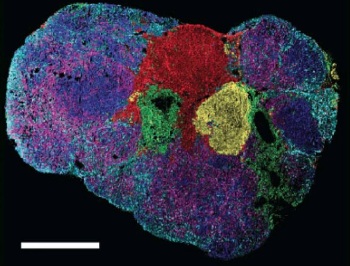

The kinetic world of metabolites comes to life in this merged overlay of mass spectrometry images. It shows new versus pre-existing metabolites in a tumor section (yellow and red indicate newer metabolites).

The kinetic world of metabolites comes to life in this merged overlay of mass spectrometry images. It shows new versus pre-existing metabolites in a tumor section (yellow and red indicate newer metabolites).

They’re part of a team of researchers that developed a mass spectrometry imaging technique that not only maps the whereabouts of individual metabolites in a biological sample, but how new the metabolites are too.

That’s a big milestone, because metabolites are constantly in flux. They’re synthesized on-demand in order to sustain an organism’s energy requirements. When you eat lunch, metabolites momentarily fire up in various cell populations throughout your body to fuel your day. But they also have a dark side. Cancer cells tap metabolites to drive tumor development.

Unfortunately, the current ways to clinically analyze metabolites don’t capture their kinetics. Microscopy maps the cells and biomarkers in a tumor section. And traditional mass spectrometry reveals the abundance and spatial distribution of molecules such as metabolites.

But these images are static snapshots of a highly dynamic process. They’re blind to how recently the metabolites were synthesized, which is a key piece of information. The metabolic status of a cell population is a good indicator of what the cells were up to when the sample was taken.

To image the ebb and flow of metabolites, the scientists paired mass spectrometry with a clinically accepted way to label tissue that uses a hydrogen isotope called deuterium.

As recently reported in Nature Scientific Reports, they administered deuterium to mice with tumors. Newly synthesized lipids (a hallmark of metabolic activity) became labeled with deuterium, while pre-existing lipids remained unlabeled. The scientists then removed tumor sections and analyzed them with a type of mass spectrometry.

The resulting images look like freeze-frames of a slow-motion fireworks show. They reveal when and where metabolic turnover occurs in a tumor section, with the brighter colors depicting newly synthesized lipids.

The scientists also found that regions with new lipids had a higher tumor grade, which is a good predictor of how quickly a tumor is likely to grow.

“Our approach, called kinetic mass spectrometry imaging, could provide clinicians with quantifiable information they can use,” says Bowen.

The scientists are now applying their imaging technique to study metabolic flux in other biological systems, such as microbial communities. This research is among several projects conducted in Northen’s lab in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division that explore the metabolism and energetics of cellular communities.