Jul 3 2013

EPFL scientists have shown how a solvent can interfere with electron transfer by using unprecedented time resolution in ultrafast fluorescence spectroscopy.

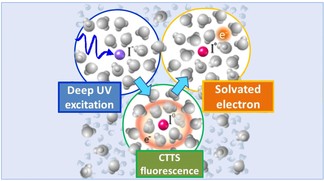

Electron transfer is a process by which an atom donates an electron to another atom. It is the foundation of all chemical reactions, and is a subject of intense research because of the implications it has for chemistry and biology. When two molecules interact, electron transfer takes place in a few quadrillionths (10-15) of a second, or femtoseconds (fsec), meaning that studying this event requires very time-sensitive techniques like ultrafast spectroscopy. However, the transfer itself is often influenced by the solution in which the molecules are studied (e.g. water), and this must be taken into account when such experiments are designed. In a recent Nature Communications paper, EPFL scientists have visualized for the first time how electron transfer takes place in one of the most common solvents, water.

For over twenty years, scientists have been trying to understand how an electron departs from an atom or molecule, travels through space in a solvent, and finally connects to an acceptor atom or molecule. Until now, experimental efforts have not borne much fruit, mostly because of the extremely short time periods involved in electron transfer. The problem is further complicated when we consider that the molecules of the commonest reaction solvent, water, are polar, which means that they respond to electron movement by influencing it. Understanding the real-time impact of the solvent is crucial, because it directly affects the outcome and efficiency of electron-transfer chemical reactions.

Majed Chergui’s group at EPFL’s Laboratory of Ultrafast Spectroscopy (LSU) employed a world-unique setup in their lab to observe the evolution of electron movement with unprecedented time-resolution. The scientists excited iodide in water with ultraviolet light, causing the ejection of an electron from the iodine atom. Using a technique called ultrafast fluorescence spectroscopy they observed the departure of the electron over different times between 60 fsec and 450 fsec. Previous research has always been limited between 200 fsec – 300 fsec because once the electron exits, other processes take place that shade the longer periods of time – and shorter timepoints have been inaccessible.

The experiment showed that the departure of the electron depends very much on the configuration of the solvent cage around the iodide. In chemistry, a ‘solvent cage’ refers to the way a solvent’s molecules configure around an atom or molecule and ‘try to hold it in place’. What the EPFL researchers found was that the polarized water molecules held the excited electron in place for a time, causing some structural re-arrangement of the solvent (water) in the process, while the driving force for electron ejection into the solvent is being reduced. Ultimately, the solvent cage does not prevent electrons from departing, but it slows down their departure stretching their residence time around iodine up to 450 fsec.

The breakthrough study shows how strongly the configuration and re-arrangement of the solvent affects electron departure. “It’s not enough to consider only the donor and acceptor of the electron – now you have to consider the solvent in between”, says Majed Chergui. “If you are thinking about driving molecules by light into electron transfer processes, this is in a way telling the community ‘watch out, don’t neglect the solvent – it is a key partner in the game, and the re-arrangement of the solvent is going to determine how efficient your reaction will be.’”