Researchers from North Carolina State University have demonstrated that vertically aligned carbon nanofibers (VACNFs) can be manufactured using ambient air, making the manufacturing process safer and less expensive. VACNFs hold promise for use in gene-delivery tools, sensors, batteries and other technologies.

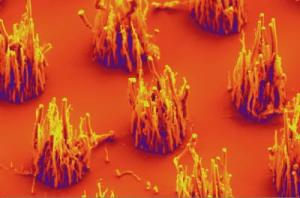

North Carolina State University researchers have shown they can grow vertically-aligned carbon nanofibers using ambient air, rather than ammonia gas. Credit: Anatoli Melechko

North Carolina State University researchers have shown they can grow vertically-aligned carbon nanofibers using ambient air, rather than ammonia gas. Credit: Anatoli Melechko

Conventional techniques for creating VACNFs rely on the use of ammonia gas, which is toxic. And while ammonia gas is not expensive, it's not free.

"This discovery makes VACNF manufacture safer and cheaper, because you don't need to account for the risks and costs associated with ammonia gas," says Dr. Anatoli Melechko, an adjunct associate professor of materials science and engineering at NC State and senior author of a paper on the work. "This also raises the possibility of growing VACNFs on a much larger scale."

In the most common method for VACNF manufacture, a substrate coated with nickel nanoparticles is placed in a vacuum chamber and heated to 700 degrees Celsius. The chamber is then filled with ammonia gas and either acetylene or acetone gas, which contain carbon. When a voltage is applied to the substrate and a corresponding anode in the chamber, the gas is ionized. This creates plasma that directs the nanofiber growth. The nickel nanoparticles free carbon atoms, which begin forming VACNFs beneath the nickel catalyst nanoparticles. However, if too much carbon forms on the nanoparticles it can pile up and clog the passage of carbon atoms to the growing nanofibers.

Ammonia's role in this process is to keep carbon from forming a crust on the nanoparticles, which would prevent the formation of VACNFs.

"We didn't think we could grow VACNFs without ammonia or a hydrogen gas," Melechko says. But he tried anyway.

Melechko's team tried the conventional vacuum technique, using acetone gas. However, they replaced the ammonia gas with ambient air – and it worked. The size, shape and alignment of the VACNFs were consistent with the VACNFs produced using conventional techniques.

"We did this using the vacuum technique without ammonia," Melechko says. "But it creates the theoretical possibility of growing VACNFs without a vacuum chamber. If that can be done, you would be able to create VACNFs on a much larger scale."

Melechko also highlights the role of two high school students involved in the work: A. Kodumagulla and V. Varanasi, who are lead authors of the paper. "This discovery would not have happened if not for their approach to the problem, which was free from any preconceptions," Melechko says. "I think they're future materials engineers."