Sep 5 2014

From the people who brought us peptoid nanosheets that form at the interface between air and water, now come peptoid nanosheets that form at the interface between oil and water.

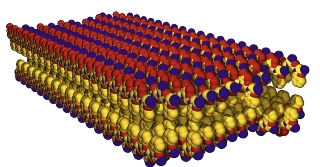

Peptoid nanosheets are among the largest and thinnest free-floating organic crystals ever made, with an area-to-thickness equivalent of a plastic sheet covering a football field. Peptoid nanosheets can be engineered to carry out a wide variety of functions.

Peptoid nanosheets are among the largest and thinnest free-floating organic crystals ever made, with an area-to-thickness equivalent of a plastic sheet covering a football field. Peptoid nanosheets can be engineered to carry out a wide variety of functions.

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE)’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have developed peptoid nanosheets – two-dimensional biomimetic materials with customizable properties – that self-assemble at an oil-water interface. This new development opens the door to designing peptoid nanosheets of increasing structural complexity and chemical functionality for a broad range of applications, including improved chemical sensors and separators, and safer, more effective drug delivery vehicles.

“Supramolecular assembly at an oil-water interface is an effective way to produce 2D nanomaterials from peptoids because that interface helps pre-organize the peptoid chains to facilitate their self-interaction,” says Ron Zuckermann, a senior scientist at the Molecular Foundry, a DOE nanoscience center hosted at Berkeley Lab. “This increased understanding of the peptoid assembly mechanism should enable us to scale-up to produce large quantities, or scale- down to screen many different nanosheets for novel functions.”

Zuckermann, who directs the Molecular Foundry’s Biological Nanostructures Facility, and Geraldine Richmond of the University of Oregon are the corresponding authors of a paper reporting these results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The paper is titled “Assembly and molecular order of two-dimensional peptoid nanosheets at the oil-water interface.” Co-authors are Ellen Robertson, Gloria Olivier, Menglu Qian and Caroline Proulx.

Peptoids are synthetic versions of proteins. Like their natural counterparts, peptoids fold and twist into distinct conformations that enable them to carry out a wide variety of specific functions. In 2010, Zuckermann and his group at the Molecular Foundry discovered a technique to synthesize peptoids into sheets that were just a few nanometers thick but up to 100 micrometers in length. These were among the largest and thinnest free-floating organic crystals ever made, with an area-to-thickness equivalent of a plastic sheet covering a football field. Just as the properties of peptoids can be chemically customized through robotic synthesis, the properties of peptoid nanosheets can also be engineered for specific functions.

“Peptoid nanosheet properties can be tailored with great precision,” Zuckermann says, “and since peptoids are less vulnerable to chemical or metabolic breakdown than proteins, they are a highly promising platform for self-assembling bio-inspired nanomaterials.”

In this latest effort, Zuckermann, Richmond and their co-authors used vibrational sum frequency spectroscopy to probe the molecular interactions between the peptoids as they assembled at the oil-water interface. These measurements revealed that peptoid polymers adsorbed to the interface are highly ordered, and that this order is greatly influenced by interactions between neighboring molecules.

“We can literally see the polymer chains become more organized the closer they get to one another,” Zuckermann says.

The substitution of oil in place of air creates a raft of new opportunities for the engineering and production of peptoid nanosheets. For example, the oil phase could contain chemical reagents, serve to minimize evaporation of the aqueous phase, or enable microfluidic production.

“The production of peptoid nanosheets in microfluidic devices means that we should soon be able to make combinatorial libraries of different functionalized nanosheets and screen them on a very small scale,” Zuckermann says. “This would be advantageous in the search for peptoid nanosheets with the molecular recognition and catalytic functions of proteins.”

Zuckermann and his group at the Molecular Foundry are now investigating the addition of chemical reagents or cargo to the oil phase, and exploring their interactions with the peptoid monolayers that form during the nanosheet assembly process.

“In the future we may be able to produce nanosheets with drugs, dyes, nanoparticles or other solutes trapped in the interior,” he says. “These new nanosheets could have a host of interesting biomedical, mechanical and optical properties.”

This work was primarily funded by the DOE Office of Science and the Defense Threat Reduction Agency. Part of the research was performed at the Molecular Foundry and the Advanced Light Source, which are DOE Office of Science User Facilities.