Mar 16 2015

Vanderbilt University researchers have achieved the first “image fusion” of mass spectrometry and microscopy — a technical tour de force that could, among other things, dramatically improve the diagnosis and treatment of cancer.

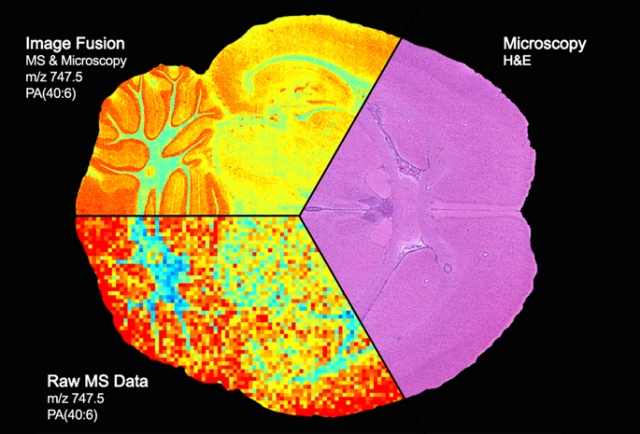

Image of a section of the brain shows the fusion of microscopy (pink area) and mass spectrometry (pixelated colors at bottom) to produce a detailed “map” of the distribution of proteins, lipids and other molecules within sharply delineated brain structures (upper left). Courtesy of Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Image of a section of the brain shows the fusion of microscopy (pink area) and mass spectrometry (pixelated colors at bottom) to produce a detailed “map” of the distribution of proteins, lipids and other molecules within sharply delineated brain structures (upper left). Courtesy of Vanderbilt University Medical Center

Microscopy can yield high-resolution images of tissues, but “it really doesn’t give you molecular information,” said Richard Caprioli, Ph.D., senior author of the paper published last week in the journal Nature Methods.

Mass spectrometry provides a very precise accounting of the proteins, lipids and other molecules in a given tissue, but in a spatially coarse or pixelated manner.

Combining the best features of both imaging modalities allows scientists to see the molecular make-up of tissues in high resolution.

“That to me is just phenomenal,” said Caprioli, the Stanford Moore Professor of Biochemistry and director of the Mass Spectrometry Research Center.

Caprioli said the technique could redefine the surgical “margin,” the line between cancer cells and normal cells where the scalpel goes to remove the tumor.

Currently that line is determined by histology — the appearance of cells examined under the microscope. But many cancers recur after surgery. That could be because what appear to be normal cells, when analyzed for their protein content using mass spectrometry, are actually cancer cells in the making.

“The application of image fusion approaches to the analysis of tissue sections by microscopy and mass spectrometry is a significant innovation that should change the way that these techniques are used together,” said Douglas Sheeley, Sc.D., senior scientific officer in the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

“It is an important step in the process of making mass spectrometry data accessible and truly useful for clinicians,” he said. The NIGMS, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), partially funded the research (grant numbers GM058008 and GM103391).

The image fusion project was led by Raf Van de Plas, Ph.D., a research assistant professor of Biochemistry who also has a faculty position at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. Other co-authors were postdoctoral fellow Junhai Yang, Ph.D., and Jeffrey Spraggins, Ph.D., research assistant professor of Biochemistry.

Using a mathematical approach called regression analysis, the researchers mapped each pixel of mass spectrometry data onto the corresponding spot on the microscopy image to produce a new, “predicted” image.

It’s similar in concept to the line drawn between experimentally determined points in a standard curve, Caprioli said. There are no “real” points between those that were actually measured, yet the line is predicted by the previous experiments.

In the same way, “we’re predicting what the data should look like,” he said.

Last year Caprioli was honored by the American Society for Mass Spectrometry for developing Imaging Mass Spectrometry (IMS) using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), a technique for visualizing proteins, lipids and other molecules in cells and tissues.

The introduction of this technology, essentially a “molecular microscope,” helps reveal the function of these molecules and how function is changed by diseases like cancer.