A new high resolution method, that uses atomic force microscopy, has been developed that allows the exact shape of a receptor and it's affinity towards a particular ligand to be measured simultaneously. This has never been achieved before and will prove extremely useful in understanding the complex mechanisms behind cell communication.

UGREEN 3S | Shutterstock

In living organisms, communication between cells is controlled by the specific intracellular and extracellular interactions that occur between hundreds of functionally different, and highly versatile receptors present in cell membranes. These receptors are unevenly distributed and are able to bind more than one signaling molecule (ligand). Receptors do display specificity but they do not work in an 'all-or-nothing' manner, receptors can sometimes weakly bind 'wrong' ligands or can ignore them altogether.

This complex receptor behavior makes it difficult for scientists to understand the signaling process. Therefore, there is an urgent need for new methods that enable accurate measurements of these highly complex interactions.

An international team of scientists, headed by Goethe University Frankfurt, have developed the first-ever, high-resolution method to enable the accurate identification and quantification of the simultaneous interactions that occur between a receptor and two ligands.

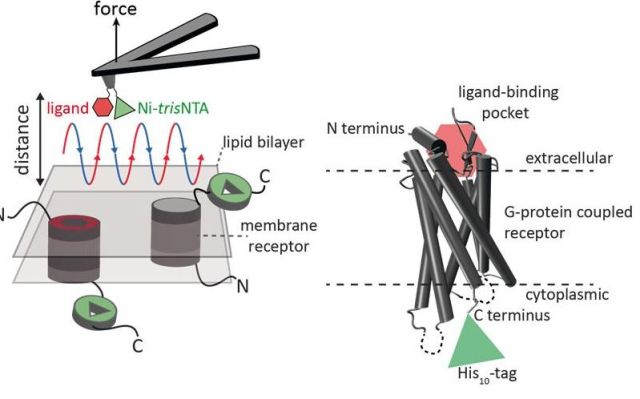

Nanoscale characterization of surfaces can be carried out effectively using atomic force microscopy (AFM). In this method, a cantilever fitted with an extremely fine tip is used. Further, high resolution images and single molecule force spectroscopy can be obtained through force-distance curve-based atomic force microscopy (FD-based AFM). The AFM tip moves towards and away from the biological samples to record each pixel.

Various coatings can be used on the AFM tip, and collectively they act as a tool box for the FD-based AFM technique. Such methods have proven to be extremely useful in the recent past. When the FD-AFM method is used to inspect specific binding sites, the ligand needs to be fastened to the AFM tip. With the help of functional AFM tips, protein complexes within a membrane can be contoured to quantify the interactions of the fastened ligand with the protein.

Page 305 - Nature Communications

Page 305 - Nature Communications

Until now it has not been possible to simultaneously capture the image of single membrane receptors whilst detecting their interactions with multiple ligands. This is now possible with the newly devised method.

In an effort to provide experimental proof of their findings, the scientists made use of the human protease-activated receptor 1 (PAR1). This receptor is part of the bigger G-protein-coupled membrane receptors (GPCRs) family. The GPCR group is largely responsible for mediating cellular responses to hormones and neurotransmitters. These receptors are also important for olfaction (smell), taste, and vision.

These receptors are capable of coexisting in various states within the cell membrane and can also bind to several ligands with varying affinities, i.e. strengths. The activation of GPCR PAR1 is done with the help of the coagulation protease thrombin, which results in a cascading of signal triggering for the initiation of cellular responses that enable thrombosis, inflammation, haemostasis and tissue repair.

The team included Ralph Wieneke and Robert Tampe from the Goethe University Frankfurt. The details of their research have been published in the current edition of the journal Nature Communications.