Oct 11 2016

New research, led by the University of Southampton, has demonstrated that a nanoscale device, called a memristor, could be used to power artificial systems that can mimic the human brain.

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) exhibit learning abilities and can perform tasks which are difficult for conventional computing systems, such as pattern recognition, on-line learning and classification. Practical ANN implementations are currently hampered by the lack of efficient hardware synapses; a key component that every ANN requires in large numbers.

In the study, published in Nature Communications, the Southampton research team experimentally demonstrated an ANN that used memristor synapses supporting sophisticated learning rules in order to carry out reversible learning of noisy input data.

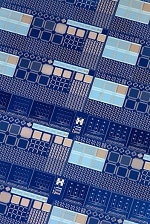

Memristors are electrical components that limit or regulate the flow of electrical current in a circuit and can remember the amount of charge that was flowing through it and retain the data, even when the power is turned off.

If we want to build artificial systems that can mimic the brain in function and power we need to use hundreds of billions, perhaps even trillions of artificial synapses, many of which must be able to implement learning rules of varying degrees of complexity. Whilst currently available electronic components can certainly be pieced together to create such synapses, the required power and area efficiency benchmarks will be extremely difficult to meet -if even possible at all- without designing new and bespoke 'synapse components'.

Memristors offer a possible route towards that end by supporting many fundamental features of learning synapses (memory storage, on-line learning, computationally powerful learning rule implementation, two-terminal structure) in extremely compact volumes and at exceptionally low energy costs. If artificial brains are ever going to become reality, therefore, memristive synapses have to succeed.

Dr Alex Serb, lead author, Electronics and Computer Science at the University of Southampton

Acting like synapses in the brain, the metal-oxide memristor array was capable of learning and re-learning input patterns in an unsupervised manner within a probabilistic winner-take-all (WTA) network.

This is extremely useful for enabling low-power embedded processors (needed for the Internet of Things) that can process in real-time big data without any prior knowledge of the data.

The uptake of any new technology is typically hampered by the lack of practical demonstrators that showcase the technology’s benefits in practical applications. Our work establishes such a technological paradigm shift, proving that nanoscale memristors can indeed be used to formulate in-silico neural circuits for processing big-data in real-time; a key challenge of modern society.

We have shown that such hardware platforms can independently adapt to its environment without any human intervention and are very resilient in processing even noisy data in real-time reliably. This new type of hardware could find a diverse range of applications in pervasive sensing technologies to fuel real-time monitoring in harsh or inaccessible environments; a highly desirable capability for enabling the Internet of Things vision.

Dr Themis Prodromakis, Co-author, Reader in Nanoelectronics, EPSRC Fellow in Electronics and Computer Science at the University of Southampton

This interdisciplinary work was supported by a CHIST-ERA net award project and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. It brought together engineers from the Nanoelectronics and Nanotechnology Group at the University of Southampton with theoretical computer scientists at the Graz University of Technology, using the state-of-art facilities of the Southampton Nanofabrication Centre.

The Prodromakis Group at the University of Southampton is acknowledged as world-leading in this field, collaborating among others with Leon Chua (a Diamond Jubilee Visiting Academic at the University of Southampton), who theoretically predicted the existence of memristors in 1971.