Mar 24 2017

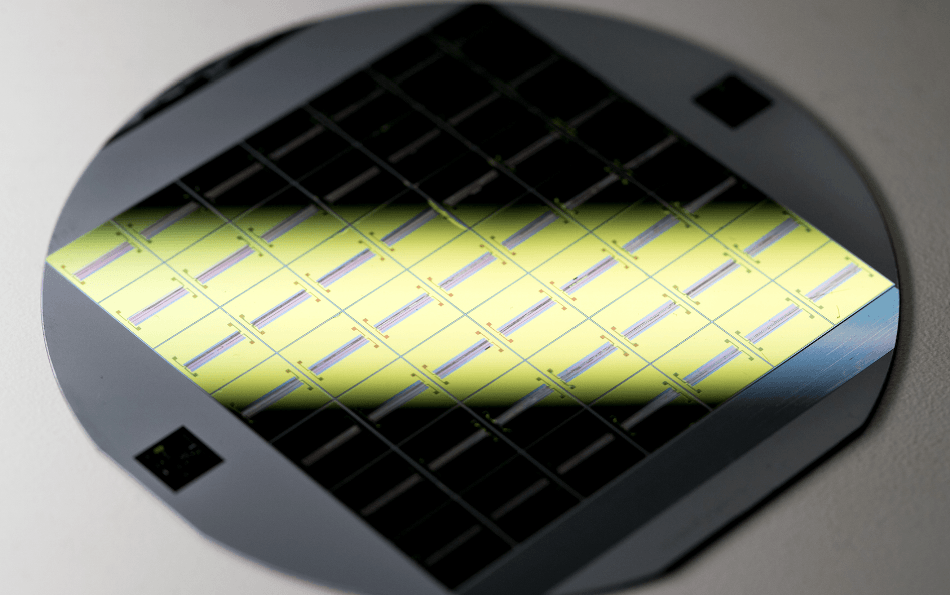

Photo Credit: Jaren Wilkey/BYU Photo

Photo Credit: Jaren Wilkey/BYU Photo

A new glass technology capable of adding a new level of flexibility to the microscopic world of medical devices has been developed by Brigham Young University researchers.

Headed by Aaron Hawkins, electrical engineering professor, the researchers discovered a technique that will bend and flex the normally brittle material of glass. This research showcases the ability to develop a new family of lab-on-a-chip devices based on flexing glass.

If you keep the movements to the nanoscale, glass can still snap back into shape. We’ve created glass membranes that can move up and down and bend. They are the first building blocks of a whole new plumbing system that could move very small volumes of liquid around.

Aaron Hawkins, Brigham Young University

The existing lab-on-a-chip membrane devices efficiently function on the microscale. However, the recently published research of Hawkins in Applied Physics Letters will permit equally efficient work at the nanoscale. The nanoscale devices can be used by biologists and chemists to move, trap and analyze extremely small biological particles like DNA, viruses and proteins.

So why work with glass? According to John Stout, lead study author and BYU Ph.D. student, glass has some great advantages: glass is solid and stiff and not a material on which things react, it is not toxic and is easy to clean.

Glass is clean for sensitive types of samples, like blood samples. Working with this glass device will allow us to look at particles of any size and at any given range. It will also allow us to analyze the particles in the sample without modifying them.

John Stout, Brigham Young University

The researchers are of the hope that their device could have the potential to carry out successful tests using smaller amounts of a substance. The glass membrane device developed by Hawkins, Stout and coauthor Taylor Welker will only need a drop or two of blood instead of several ounces to perform a blood test.

Hawkins stated that the device should allow rapid analysis of blood samples: “Instead of shipping a vial of blood to a lab and have it run through all those machines and steps, we are creating devices that can give you an answer on the spot."

In the healthcare industry, there is a growing demand for portable on-site rapid testing. Much of this is being realized through these microfluidic devices and systems, and this testing could be taken to the next level of detail by the BYU device.

“This has the promise of being a rapid delivery of disease diagnosis, cholesterol level testing and virus testing,” Hawkins said. “In addition, it would help in the process of healthcare knowing the correct treatment method for the patient.”